What is this? This newsletter aims to track information disorder largely from an Indian perspective. It will also look at some global campaigns and research.*

What this is not? A fact-check newsletter. There are organisations like Altnews, Boomlive, etc. who already do some great work. It may feature some of their fact-checks periodically.*

Welcome to Edition 25 of MisDisMal-Information

Note: Since I was away with limited connectivity over the last couple of weeks, this edition will be different. Instead of going wide (since I haven’t been able to track things the way I normally do), I will focus on the specific topic of regulating information disorder.

There was a lot of concern over the weekend as Kerala’s Governor gave his assent to an ordinance to amend the Kerala Police Act ostensibly in response to rising information disorder and defamatory attacks on women and children. But it appears, for now, that is legislation has been put on hold.

If you’ve been following developments around the world and in India over the last few months, though, you know that this is likely only a temporary reprieve. Back in October, IFF had noted its similarities to the infamous section 66A which was struck down. In TheNewsMinute, Sanyukta Dharmadhikari compares 118A with 66A using a side-by-side comparison shared by Anivar Aravind.

And even with the developments on Monday, IFF is right to advise caution.

The bullet may have been dodged, but the incoming train is still chugging along.

I’ve ended up devoting space over multiple editions to arrests/FIRs in India over “spreading fake news”. These do not appear to be limited to any specific part of the country or political party. I had amassed a 31 tweet thread in just a few weeks of tracking ‘fake news’ and ‘rumour mongering’ arrests/FIRs in June.

And here’s a quick recap of solutions to address information disorder just from previous editions:

Executive issued rules ranging from “banning social media” (edition 9), “holding WhatsApp admins culpable” (edition 6)

‘Fact Finding’ reportssubmitted to the Home Minster recommending ‘real time social media monitoring’ (edition 8)

There are probably many others that I’ve missed. If you know off them - please reach out to me on Twitter

Even the developments in Kerala have been on the cards for months now as we’ve seen in previous editions - from accusations of ‘Trumpian’ behaviour of condemning ‘unfavourable news’ as ‘fake news’ by the opposition, pushback against fact-checking initiatives and actual arrests under the various acts including the Kerala Police Act. In fact, just like this weekend, even back in September, the Chief Minister was reassuring people that

Edition 15 (August)

Edition 16 (August)

Edition 17 (September)

Edition 20 (September)

Edition 22 (October)

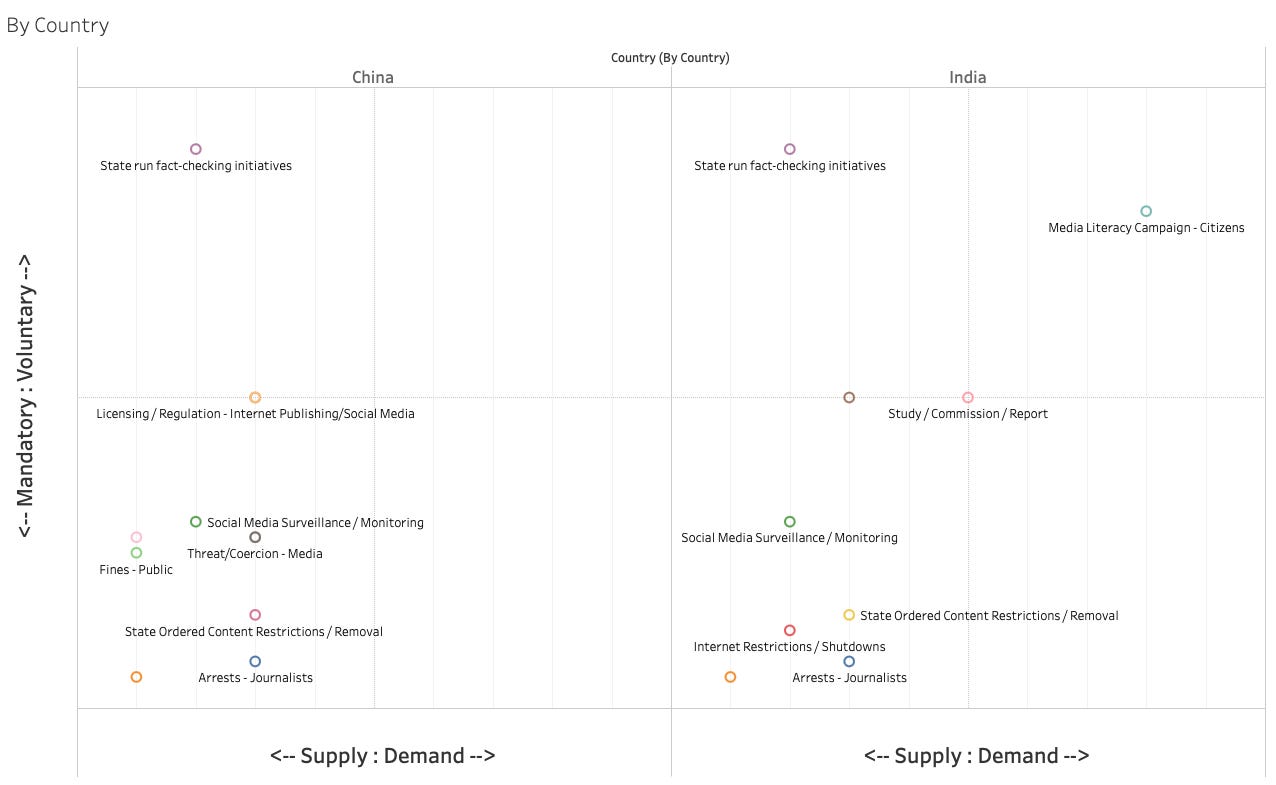

In Edition 19, we looked at how there was a tendency across many countries to resort to measures that were “mandatory” and dealt with the “supply-side of the problem.

By this classification, look at how similar India and China seem to be: I will admit that this framework is not without its limitations as of now.

But for today, let’s explore what considerations should actually go into regulating information disorder. I am going to draw heavily from chapters written by Heidi Tworek and Ben Epstein in the open access book ‘The Disinformation Age’ and Richard Allan’s posts (1 and 2) on a ‘misinformation regulator’. We’ll keep in mind all through that the former were written from the U.S. perspective, and the latter for the United Kingdom.

Both Tworek and Epstein acknowledge that there are no simple solutions - and we should stop looking at the problem as if they exist. This is a gripe I have with our culture of trying to force-simplify problems when addressing “people who are too busy” since it leads to a massive loss of nuance - the effects of which can vary from harmless to being very dangerous. But that is a topic for another day.

Tworek begins with a warning about the novelty hype in that, we tend to consider that the current circumstances are unique and proposes that we end up missing the following as a result of this.

Path dependency of the Internet.

Misdiagnose issues as content problems rather than situating them in the broader context of international relations, economics and society.

Focus on the day-to-day rather than underlying structures.

Think short-term instead of the long-term and unintended consequences of regulation.

Hark back to past “golden age” that never was.

The algorithmic bias toward anger is new; our anger-inspired analytical biases are not. Social media may amplify anger, but that anger also stems from real-world experiences of current conditions.

She then goes on draw lessons from the past - specifically Germany in the inter-war period.

Disinformation is also an international relations problem.

Physical infrastructure matters.

Business structures are often more important than individual pieces of content

The need for robust regulatory institutions and to “democracy-proof” solutions so they cannot be bent by the powers of the day.

Solutions should address societal divisions that media is used to exploit.

She also sounds a number of warning throughout the chapter:

the focus on the next election and the short-term can obscure the long-term consequences of regulatory action. Often the most import- ant developments take years to understand. Talk radio in the United States is a good example; another is the unintended consequences of spoken radio regulation in Weimar Germany. Bureaucrats aimed to save democracy by increasing state supervision over content. This was meant to prevent seditious material that would bolster anti-democratic sentiment and actions. Ironically, however, these regulations ensured that the Nazis could far more swiftly co-opt radio content once they came to power in January 1933. Well-intentioned regulation had tragic, unintended consequences.

A historical view reminds us that any media legislation has to stand in the long term. Some might like a hate speech law requiring removals under President Emmanuel Macron; but would they like it under a President Marine Le Pen?

Other suggestions specifically for social media include regulating for transparency before intervening in content. … Such proposals are less interventionist than many other suggestions and less appealing to many clamoring for the regulation of content. … But it is worth considering whether less interventionist solutions will better uphold democracy in the long run. It is also worth considering whether much of the abuse is enabled by the particular business models of social media and the lack of incentives to enforce their terms of service, which often already ban the behavior of abusive users.

Mind-map summarising Tworek’s chapter

Epstein begins with quoting a report from the Eurasia Center that sums up the intractability of the problem.

As a report from the Eurasia Center, a think tank housed within the Atlantic Council argues, “There is no one fix, or set of fixes, that can eliminate weaponization of information and the intentional spread of disinformation. Still, policy tools, changes in practices, and a commitment by governments, social-media companies, and civil society to exposing disinformation, and building long-term social resilience to disinformation, can mitigate the problem.”

And,

As this complex problem has gained greater attention, proposed interventions have spread at 5G speed.

He identifies 3 challenge to regulation of online disinformation. But before we go there - let’s consider the 0th question and 0.5th question.

0: Should we regulate this?

This is not a question that I alone can answer. 4-5 years ago, many people would have said no, today - many people will probably say yes. 4-5 years from now? - we don’t know.

For now, let’s assume that we do choose to regulate this. Then it is important to call attention to the reality that in trying to regulate disinformation, we can create structures that enable the (further) regulation of all information.

0.5: Do we need new laws?

Given that I have no legal training, I will not attempt to answer to this myself. An editorial in Times of India (23rd November 2020) remarks:

This penchant for legislating new laws while neglecting existing ones is a peculiar Indian trait. The solution for police failure to address vicious cyberbullying or cyberstalking is to improve responsiveness and technological capabilities. The LDF government’s shrinking political capital amid multiple central agency probes and inability to control the media narrative may explain the timing. Assent from the governor, a central appointee, is evidence that neither Left nor Right have much patience for dissent or parliamentary scrutiny. Both the Left and Right ends of the political spectrum are squeezing constitutional liberties in the middle. Netas, please spare a thought for harried citizens, increasingly getting boxed between sedition-like laws or statist paternalism to save them from non-existent “love jihad”.

While political theatre of this sort is not uniquely Indian, multiple governments (State and Union) have exhibited a propensity to enact new laws when the solution lies somewhere between building capacity and enforcing existing laws.

Again, for the sake of argument, let’s assume we have a healthy debate (what? I can dream. Can’t I?) across different stakeholders and agree that state regulation is the way forward (we’ll briefly address self-regulation a little later on).

Alright, now let’s get back to Epstein’s challenges.

Defining the problem in a way that allows regulators to distinguish between the different types of false information.

Here, Epstein draws on Clair Wardle’s Information Disorder framing (see Edition 1) and concludes that disinformation is better suited for regulatory laws and legal action, since you can potentially identify ill-intent. He does not necessarily suggest different approaches for economic v/s political motives.

Aside: When you consider the information ecosystem and pollution framing (as I often do) it can be tempting to disregard intentions (indeed, they are not often easy to establish either). However, when considering punitive measures - limiting the scope by intent is a useful guardrail to start with. In other words,

Clean the ecosystem, regulate and/or prosecute for intent/disinformation

Who should control the regulation?

Government regulation v/s self regulation. For many, it seems the self-regulation option is closed - and that’s in part down to the actions (or inactions - depending on how you look at it) of the platforms themselves. But COVID-19 and the US Elections have demonstrated that platforms can act (whether these actions are effective is another topic) when incentives are created for them to do so (in this case, likely political pressure). And so, while I don’t believe that the option is closed for good - the likelihood of systemic changes to incentives without a state-backed push, in the timeframe we want (yesterday!) seems unlikely.

But, if you go back to Tworek’s warnings about state control - and if you just look around - it is clear that the information ecosystem is too important to be controlled by an unfettered state.

Here, Epstein offers a middle-ground of sorts in the form of independent commissions:

The options for control are not a binary choice between autonomous self-regulation by the powerful platforms themselves and legislation handed down by national or international governmental bodies. Independent commissions are likely going to play an important role in the regulation of disinformation moving forward because they can have greater impartiality from government or corporate control; can potentially act more nimbly than governments; and can have the authority to hold companies or individuals accountable.

What would effective regulation look like?

Epstein refers back to guideposts inferred from Tworek’s chapter.

And adds:

Regulatory teeth should be proportional to the harms found. i.e. Any penalties imposed should actually pinch the offending organisations unlike what we’ve seen so far.

He cites the UK recommendation for an independent regulator that can

draw up codes of conduct for tech companies, outlining a new statutory “duty of care” toward their users, with the threat of penalties for noncompliance including heavy fines, naming and shaming, the possibility of being blocked, and personal liability for managers.

I’ll digress slightly at this point to look at Richard Allan’s proposal for such a regulator.

He also recommends that this regulator be “an arms-length body rather than a formal arm of the state” but concedes that debate on whether a body can be independent if it is state regulated is far from settled.

His model has 3 stages - assess validity, which would involve some form of public reporting. Those reports deemed not harmful can be rejected, those concerning other jurisdictions may need to be passed along (assuming some sort diplomatic arrangements).

Reports considered in scope will be investigated further. It is notable that this model favours directing claims to existing regulators/bodies where possible to avoid regulatory overlap and does not envision punitive powers - but only advisory functions in the claims it does process on its own.

Summary of Richard Allan’s Misinformation Regulator proposal

To conclude - Epstein lays down 4 principles for such regulation:

First, is a regulatory Hippocratic oath: disinformation regulation should target the negative effects of disinformation while minimizing any additional harm caused by the regulation itself.

Second, regulation should be proportional to the size of the harm caused by the disinformation and the economic realities of the companies potentially subject to regulations.

Third, effective regulation must be nimble, and able to adapt to changes in technology and disinformation strategies more than previous communication regulations.

Fourth, effective regulations should be determined by independent agencies or organizations that are guided by ongoing research in this field.

And now, just square these with the measures we’ve seen so far.

Also - on the topic of today’s edition

Nina Jankowicz writes in Foreign Affairs about how the Biden Administration can take on disinformation. I’ve included some excerpts here.

creating a counter-disinformation czar within the National Security Council and setting up a corresponding directorate. This office would monitor the information ecosystem for threats and coordinate interagency policy responses.

…

Biden should lean on his bipartisan track record and encourage Congress to establish a federal commission for online oversight and transparency. Such a commission would make sure that social media platforms guard against malign foreign content and don’t fall prey to partisan bias

…

Congress must recognize that disinformation is not a partisan issue or risk further neglecting its duty to protect democratic norms and practices.

…

Serious efforts to combat disinformation will require a commensurate budget. The Biden administration should look to allies that have decades of experience dealing with disinformation. Some European countries have made generational investments in building media and digital literacy programs for both students and voting-age adults.

…

bolster public media in order to provide more sober alternatives to the fire and brimstone of cable news.

And Kyle Daly speaks to Karen Kornbluh, Dipayan Ghosh and Alex Stamos about the Biden administration’s day 1 challenges.

A less dysfunctional approach to managing the pandemic by the Biden administration could help reset the misinformation environment, Karen Kornbluh, a former Clinton and Obama administration official who is now director of the German Marshall Fund’s Digital Innovation and Democracy Initiative, told Axios.

“There’s a real opportunity to start getting people to feel more civic-minded and also help them understand how to get access to trusted information,” she said.

Such an effort could include something like a “digital version of FDR’s fireside chats walking people through the facts, the latest developments, and what they need to do to get through the emergency together.”

I’ll be honest, the last one sounded like Mann Ki Baat to me.

Obama White House veteran and former Facebook policy staffer Dipayan Ghosh has suggested : The administration could strike an agreement with industry to share data on disinformation campaigns as they’re spreading.

And on medical misinformation:

“Obviously, disinformation around the election is important, but disinformation about the vaccine will have a body count,” Alex Stamos, former Facebook security chief and head of the Stanford Internet Observatory, told Axios.

One idea for stemming the damage: Stamos suggests designating vaccine distribution as critical infrastructure. That would authorize government cyber operators to monitor for disinformation and work with federal, state and local officials to stamp it out.

Ok, so let me ask you this - can you think of a single solution to deal with our information ecosystem woes?

If that question sent you down into a tunnel of despair - then, congratulations, you’ve been paying attention. There is much work to be done.