Of Q-A-Gone, Laughter, Models and Roles

MisDisMal-Information Edition 22

What is this? This newsletter aims to track information disorder largely from an Indian perspective. It will also look at some global campaigns and research.*

What this is not? A fact-check newsletter. There are organisations like Altnews, Boomlive, etc. who already do some great work. It may feature some of their fact-checks periodically.*

Welcome to Edition 22 of MisDisMal-Information

Q-A-gone

This is one of the few occasions I won’t be starting off with an India-centric bit. And while the context maybe foreign, I think the ideas still apply

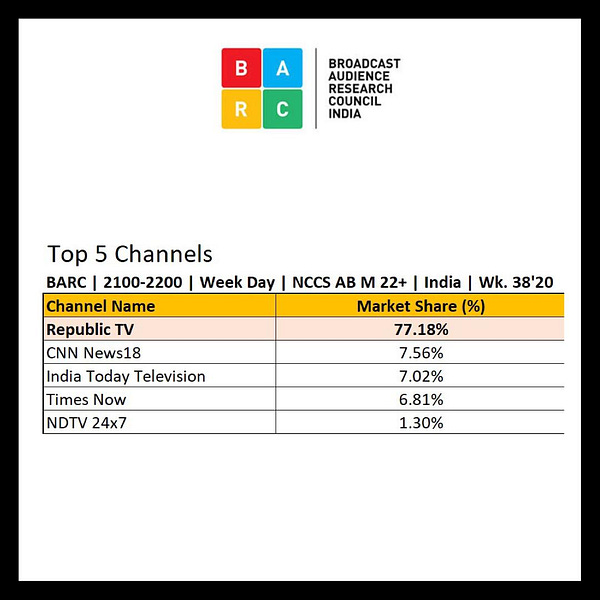

Well, it happened, Facebook went after QAnon (again), but seemingly with more intent this time.

In the first month, we removed over 1,500 Pages and Groups for QAnon containing discussions of potential violence and over 6,500 Pages and Groups tied to more than 300 Militarized Social Movements. But we believe these efforts need to be strengthened when addressing QAnon.

Starting today, we will remove any Facebook Pages, Groups and Instagram accounts representing QAnon, even if they contain no violent content. This is an update from the initial policy in August that removed Pages, Groups and Instagram accounts associated with QAnon when they discussed potential violence while imposing a series of restrictions to limit the reach of other Pages, Groups and Instagram accounts associated with the movement. Pages, Groups and Instagram accounts that represent an identified Militarized Social Movement are already prohibited.

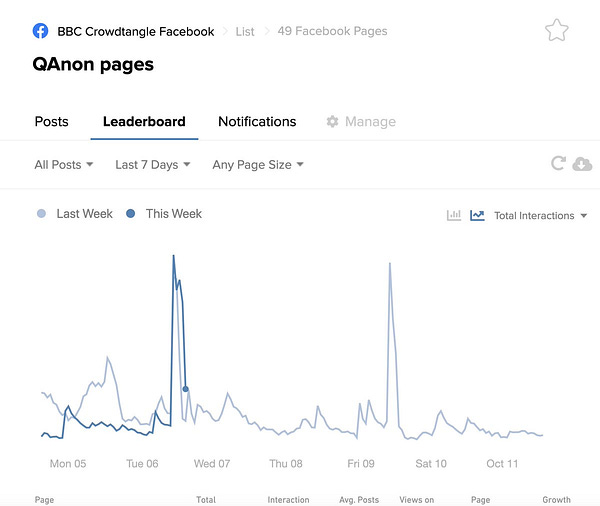

Shayan Sardarizadeh, who has been monitoring various groups and doing a weekly thread “this week in qanon” (see Twitter Search) has seen a big drop in the number of groups/pages/profiles he was tracking.

For all intents and purposes, this is a good thing. Though, such conspiracy theories are a hybrid stock-and-flow problem. Such interventions, mainly address the “stock”. They may stem the flow for a short period - but by now, we should know all too well that such movements adapt. All the way back in Edition 12, there was a piece by Abby Ohlheiser about fact-checks and account bans not being enough to stop QAnon.

As of the time I am writing this (Thursday evening in India), no similar announcement from other platforms have been made (some times these things tend to happen in spurts, or fall like dominoes). One domino seems to have fallen, and it was certainly one I didn’t expect. Etsy says it will remove QAnon-related merchandise. Q-ware (I totally made that term up) has been around on various e-commerce platforms, as this articlefrom mid-August indicates. How much it sells? That I really don’t know

We’ve also been here before, sort of. Just 3 weeks ago, Sheera Frenkel and Tiffany Hsu wrote in the New York Times about Facebook QAnon ban 1.0 not being effective enough.

The QAnon movement has proved extremely adept at evading detection on Facebook under the platform’s new restrictions. Some groups have simply changed their names or avoided key terms that would set off alarm bells. The changes were subtle, like changing “Q” to “Cue” or to a name including the number 17, reflecting that Q is the 17th letter of the alphabet. Militia groups have changed their names to phrases from the Bible, or to claims of being “God’s Army.”

Others simply tweaked what they wrote to make it more palatable to the average person. Facebook communities that had otherwise remained insulated from the conspiracy theory, like yoga groups or parenting circles, were suddenly filled with QAnon content disguised as health and wellness advice or concern about child trafficking.

And, then of course, there’s the likelihood of this content being recommended organically.

From the same piece:

Perhaps the most jarring part? At times, Facebook’s own recommendation engine — the algorithm that surfaces content for people on the site — has pushed users toward the very groups that were discussing QAnon conspiracies,

The Guardian reports that Facebook has missed some high-profile Australian accounts linked to it.

Kaitlyn Tiffany covers how Reddit got lucky by essentially getting rid of QAnon.

Unfortunately, Reddit is not particularly good at explaining how it accomplished such a remarkable feat. Chris Slowe, Reddit’s chief technology officer and one of its earliest employees, told me, point-blank: “I don’t think we’ve had any focused effort to keep QAnon off the platform.”

In a nutshell, it took action against subreddits for doxxing and got very lucky on the timing.

This isn’t a Facebook-only though problem by any means. Around the same time, Clive Thompson, in WIRED, wrote about the role of YouTube’s Up Next in sending people down the conspiracy theory, information disorder rabbit-hole and their travails with ‘borderline content’ - the term used to describe content that is close to be being against some policy or the other, but not quite there - and not quite very well defined as the article points out.

In 2018 a UC Berkeley computer scientist named Hany Farid teamed up with Guillaume Chaslot to run his scraper again. This time, they ran the program daily for 15 months, looking specifically for how often YouTube recommended conspiracy videos. They found the frequency rose throughout the year; at the peak, nearly one in 10 videos recommended were conspiracist fare.

In 2019, YouTube starting rolling out changes and claimed that it had reduced the watch-time of borderline content by 70%. Claims that couldn’t be independently verified, but the downward trend seems evident.

Berkeley professor Hany Farid and his team found that the frequency with which YouTube recommended conspiracy videos began to fall significantly in early 2019, precisely when YouTube was beginning its updates. By early 2020, his analysis found, those recommendations had gone down from a 2018 peak by 40 percent.

And then came the pandemic, and QAnon:

“If YouTube completely took away the recommendations algorithm tomorrow, I don’t think the extremist problem would be solved. Because they’re just entrenched,” [Becca] Lewis tells me. “These people have these intense fandoms at this point. I don’t know what the answer is.”

One of the former Google engineers I spoke to agreed: “Now that society is so polarized, I’m not sure YouTube alone can do much,” as the engineer noted. “People who have been radicalized over the past few years aren’t getting unradicalized. The time to do this was years ago.”

I have 2 points to make here.

Recommendation Engines: This paper by Jennifer Cobbe and Jatinder Singh asserts that:

Focusing on recommender systems, i.e. the mechanism by which content is recommended by platforms, provides an alternative regulatory approach that avoids many of the pitfalls with addressing the hosting of content itself.

collectively, these studies and investigations show that open recommending can play a significant role in the dissemination of disinformation, conspiracy theories, extremism, and other potentially problematic content. Generally, these recommender systems do not deliberately seek to promote such content specifically, but they do deliberately seek to promote content that could result in users engaging with the platform without concern for what that content might be.

They make the point that while a safe-harbour regime like hosting is the likely response (or was anyway), the task of recommending involves higher discretion and therefore should be accompanied with more responsibility. And that while regulation pertaining to content transmission and hosting can raise freedom of expression concerns, a regulatory approach focused on the recommendation engine can “side-step” that since the “onward algorithmic dissemination and amplification of such content by service providers would be the focus of regulation”

The paper proposes 6 principles that certainly merit some further thought.

Open recommending [recommendation on user generated content platforms like Facebook/YouTube/TikTok etc) must be lawful and service providers should be prohibited from doing it where they violate these principles or other applicable laws.

Service providers should have conditional liability protections for recommending illegal user-generated content and should lose liability protection for recommending while under a prohibition.

Service providers should have a responsibility to not recommend certain potentially problematic content.

Service providers should be required to keep records and make information about recommendations available to help inform users and facilitate oversight.

Recommending should be opt-in, users should be able to exercise a minimum level of control over recommending, and opting-out again should be easy.

There should be specific restrictions on service providers’ ability to use recommending to influence markets through recommending.

And, secondly, as this article by Abby Ohlheiser states - it didn’t have to be this way. She spoke with the likes of Shireen Mitchell, Katherine Cross, Ellen Pao who had seen the warning signs early [targeted harassment, abuse] and even experienced them but were not taken seriously at the time. *In Edition 5, I linked to an episode of TheLawfare Podcast featuring Danielle Citron, where she had the made the point that vulnerable groups are where we see the harms first.* The crux is this:

I’m not proposing to tell you the magical policy that will fix this, or to judge what the platforms would have to do to absolve themselves of this responsibility. Instead, I’m here to point out, as others have before, that people had a choice to intervene much sooner, but didn’t. Facebook and Twitter didn’t create racist extremists, conspiracy theories, or mob harassment, but they chose to run their platforms in a way that allowed extremists to find an audience, and they ignored voices telling them about the harms their business models were encouraging.

And this is where I’ll bring it home. We’ve seen platforms respond (I am deliberately not saying intervene) in the U.S and Western Europe far faster (it is relative of course) than we have seen in the ‘Global South’. That they continue to lack (or seem to anyway) the know-how to intervene meaninfully in places like India - is a choice.

Is Laughter the best medicine?

There was one quote from the last article that also struck me, and it is linked to the ‘killjoy’ spree I have been on for the last few editions (emphasis added).

Whitney Phillips, an assistant professor at Syracuse University who studies online misinformation, published a report in 2018 documenting how journalists covering misinformation simultaneously perform a vital service and risk exacerbating harmful phenomena. It’s something Phillips, who is white, has been reckoning with personally. “I don’t know if there’s a specific moment that keeps me up at night,” she told me, “but there’s a specific reaction that does. And I would say that’s laughter.” Laughter by others, and laughter of her own.

This goes back to the ‘not just a joke’ aspect I covered in Edition 21 and the utility of parody from Edition 18. Whether we like to admit or not, humour has been weaponised - and even harder to admit: we all likely participate in it.

Whether it is mocking someone for “taking a dramatic fall” somewhere between New Delhi and Hathras, or ridiculing another someone for waving at an empty tunnel (or camera lenses?) - the effect on the information ecosystem is the same.

Come on, Prateek! It was funny!

Yes, one of them probably was. Let’s think about this for a second though, in a world where even some of the most valuable companies in the world claim to be competing for our attention, what is the opportunity cost of such distraction whether it is for humour or outrage? Ok, enough preaching.

Conspiracy, Conspiracy, Conspiracy

Let’s start with the Sushant Singh Rajput case:

The Mumbai Police claims to have found over 80,000 ‘fake accounts’ who tweeted about this case to discredit them. You’ll notice my tone is one of caution. That’s because I have questions. I don’t doubt that there were likely many inauthentic accounts - some analysis in this very newsletter points in that direction. But at these numbers, it is important to understand - how was fake defined (it is critical to know what criteria were used), what tools were used (many known ‘bot detectors’ do have significant false positive rates). Many researchers advise that behaviour which seems suspicious at an aggregate level, needs to be verified manually. We don’t really know what happened here. The article also mentions relevant sections of the IT ACT. I am very curious about which these sections are and if there are any implications for the use pseudonymous accounts.

Kunal Purohit details the role of online groups in stoking anger around this case for Article 14. Some things to note: the relative numbers between QAnon group memberships and SSR groups. Spoiler Alert: In terms of numbers, the latter seems significantly larger. I should disclose that it includes from quotes from me as well. In addition to a number of examples, it also features a report by the team (Syeda Zainab Akbar, Ankur Sharma, Himani Negi, Anmol Panda and Joyojeet Pal) at Microsoft Research. From the report’s conclusion:

The array of stakeholders, each with their own interests in moving the story forward, are an important part of what has driventhis to the point of being perhaps the top national story, despite being in the middle of the worst pandemic and economic crisisIndia has known. The timing of the suicide, in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis and lockdown with many urban middle-classIndians stuck at home, probably had a role in driving up purchase for the story.

Then, there is good old fashioned hate on new media.

In another Article 14 article, Shweta Desai takes a journey into the accounts of currently-part-of-fringe-but-probably-mainstream-in-the-future-social-media-personalities-🤷♂️. And yes, it included the Dangerous Speech Project, too

A closer analysis of 10 of these fringe accounts, which are part of the online right-wing network and have between 700 to 35,000 followers, revealed that despite the content visibly violating Facebook’s policies on dangerous hate speech, many remain publicly visible even today.

Shifting attention to Hathras now:

In ThePrint, Angana Chakrabarti and Revathi Krishnan recount the conspiracies that Republic TV, News 18 and Zee News are seeing.

The UP Government claims in the Supreme Court, that ‘fake news’ is being peddled to the malign the state.

A different and false narrative has started gaining momentum at the behest of some vested interests on social media by attributing baseless comments and building up a distorted narrative on the Hathras case, the state told the SC. “Sections of the media are deliberately interfering with the process (investigation) and not permitting the truth to be unveiled and the guilty punished,” the state added.

The affidavit cited “diverse examples of fake news from across the country and from fake and verified handles from people of different political spectrums”, to “clearly” point “towards a conspiracy fomented by rival political parties to defame and discredit” the state government.

21 FIRs have also been filed by the UP Police for “spreading fake information, violating the prohibitory orders and Covid-19 guidelines”

A Journalist and 3 others were booked for sedition, as well as under the UAPA and IT Acts.

accuses the four of carrying pamphlets reading ‘Justice for Hathras Victim’ and moving towards the district to disrupt peace as part of a “big conspiracy”.

Meanwhile in India

Shannon Vavra and Sean Lyngaas for Cyberscoop about a Chinese operation that includes targets in India among other countries:

The revelation comes after U.S. Cyber Command , the Pentagon’s offensive hacking unit, and DHS’s Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency (CISA) released information about the malware on Oct. 1, but did not attribute the campaign. A Pentagon spokesperson told CyberScoop the hacking effort is ongoing, and that it has targeted entities in Russia, Ukraine, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Malaysia. (Officials did not specify which types of organizations the campaign has targeted.)

Cyber Command and CISA declined to comment on attribution.

If you’re a regular reader, you know there’s generally a section covering threats/coercion/arrests for spreading ‘fake news’. This week doesn’t disappoint either.

Arrest them all…

In Kerala, the cyber police has filed over 200 cases for ‘fake news’ (Can we please stop using that term, so that I can stop using it too?). Cases were filed under the Information Technology Act, Kerala Police Act, and the Pandemic Act.

The Mumbai Police has registered 37 FIRs, arrested 32 people and classified 29 people as ‘wanted’ including taken ‘immediate action’ in 43 cases that were of ‘extreme nature’.

“We are continuously monitoring social media platforms and actions are initiated for instigating and spreading rumours through these channels. “

And, also:

Sleuths of the Navghar police in Bhayandar have registered a FIR against a youth for fake and objectionable post about human organ trafficking and spreading rumours about Covid-19 tests

In Rajasthan, FIRs have been lodged against a journalist and Sachin Pilot’s media advisor for, you guessed it, “spreading fake news” during the power tussle between the Chief Minister and Deputy Chief Minister.

In Andhra Pradesh, “The police noticed that some people circulated fake news on desecration of a religious place in Narasaraopet. The fake news was about alleged desecration of Saraswati idol at Krishnaveni College premises in Narsaraopet town.”

Police department will not tolerate such activities and stern action will be taken against the wrongdoers. Police department appeals to all the citizens that they should exercise caution and check the veracity of the news before sharing it.

Propagating such false news causes damage to individuals, religious sects, political setup and even the community at large, said the State police office on Wednesday.

In Tripura, the “Tripura Assembly of Journalists” wrote to the Prime Minister and Union Home Minister after “at least 6” journalists were attacked across the state. They linked it to the Chief Minister’s remarks

“Neither history will forgive them nor will I forgive them. These media houses and newspapers are spreading fake news and scaring people.” Deb also claimed that the media was confusing people of Tripura with their “overexcited reporting”.

BJP’s general secretary has branded opposition party politics around the farm bills as “disinformation” and that it amounted to “criminal conduct”.

And…

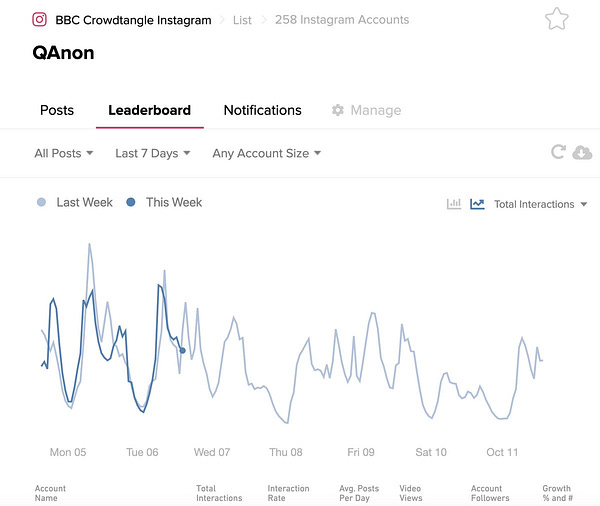

An interesting observation by Joyojeet Pal on the impact of political affiliation of lead stars on crowd-sourced ratings (like IMDB).

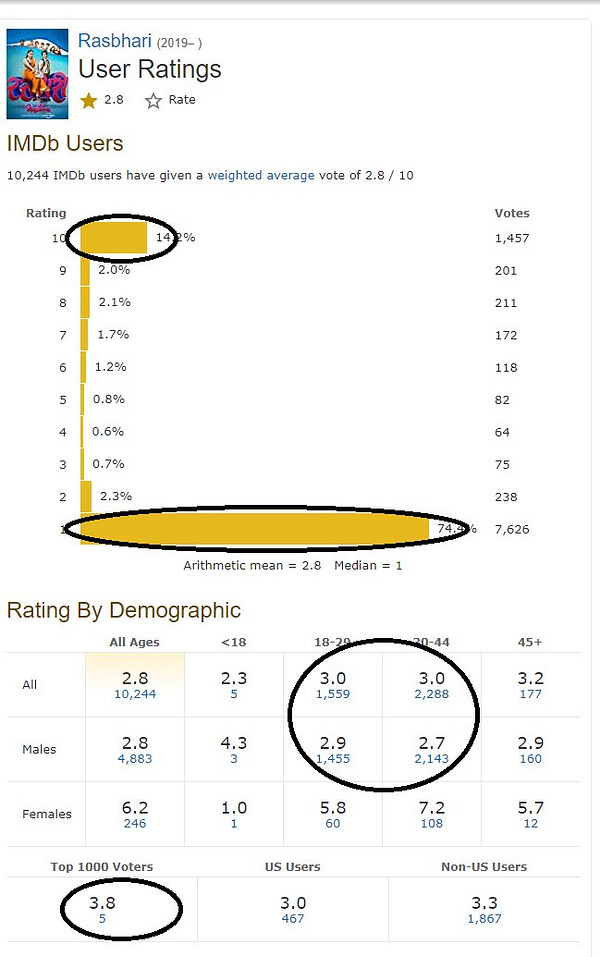

You can’t make this up, a day after Union I&B Minister called out TRP-driven news channels. Republic TV did this:

And then, the Mumbai Police did this:

And then, Twitter did this:

And I did this:

The Models and Roles

These are themes we’ve visited before in this newsletter, so I’ll avoid repeating myself.

The Business Model

A lot has already been said about how the business models of social media platforms incentivise conflict. An upcoming book “Subprime Attention Crisis”, Tim Hwang argues that the behavioural targeting doesn’t work. Gilead Edelman reviews it for WIRED.

Funny story about this tweet (yes, I am featuring my own tweets again) -

The role of the traditional information intermediary

In a ‘matter of frames’ in Edition 21, I wrote about the role of the traditional media in the current state of the information ecosystem, and any efforts to remedy the situation.

Well, you’ve already seen the TRP kerfuffle earlier in this edition.

An opinion piece in Independent claims that newspapers are the defence against ‘fake news and misinformation’.

But then, see this column [paywall] by Margaret Sullivan arguing that the mainstream media does the job of spreading Trump’s disinformation.

Eager to look neutral — and worried about being accused of lefty partisanship — mainstream news organizations across the political spectrum have bent over backward to aid and abet Trump’s disinformation campaign about voting by mail by blasting his false claims out in headlines, tweets and news alerts, according to the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University.

Link to the original study in the next section

Staying with Trump, Sean Illing says that coverage post his COVID-19 diagnosis was far from ideal.

Is Trump faking it so that he can pretend to have recovered and thus prove the virus isn’t dangerous? Or maybe he’s floating the story in order to divert attention away from his tax scandal or his chaotic debate performance . Or maybe the “deep state” deliberately infected Trump to undercut his reelection campaign. Or the White House is using this as an excuse to get out of the next debate.

These days, when something important or “newsy” happens, there’s an avalanche of content online that overwhelms people and leaves them less certain of what’s happening than before. In this case, we had a single news event — the president tested positive for the coronavirus — that set off a flood of disorienting bullshit bouncing around the information space.

And Yochai Benkler, one of the authors of the study mentioned earlier, writes about ‘How not to cover voter fraud disinformation’.

Contrary to widespread concern with Russia or Facebook as vectors of election disinformation, our findings told a different story.

President Trump perfected the art of harnessing mass media to disseminate and reinforce his disinformation campaign. As president, his statements command attention, and his frequent norms-breaking statements are like clickbait for journalists.

treating the falsehoods no differently than they would if their source were Russian propagandists or Facebook clickbait artists.

Studies/Analyses

Continuing with the Berkman Klein Center study:

Our results are based on analyzing over fifty-five thousand online media stories, five million tweets, and seventy-five thousand posts on public Facebook pages garnering millions of engagements.

Donald Trump has perfected the art of harnessing mass media to disseminate and at times reinforce his disinformation campaign by using three core standard practices of professional journalism. These three are: elite institutional focus (if the President says it, it’s news); headline seeking (if it bleeds, it leads); and balance , neutrality, or the avoidance of the appearance of taking a side.

The president is, however, not acting alone. Throughout the first six months of the disinformation campaign, the Republican National Committee (RNC) and staff from the Trump campaign appear repeatedly and consistently on message at the same moments, suggesting an institutionalized rather than individual disinformation campaign. The efforts of the president and the Republican Party are supported by the right-wing media ecosystem

And the kicker (emphasis mine):

The primary cure for the elite-driven, mass media communicated information disorder we observe here is unlikely to be more fact checking on Facebook. Instead, it is likely to require more aggressive policing by traditional professional media, the Associated Press, the television networks, and local TV news editors of whether and how they cover Trump’s propaganda efforts

A report by Cécile Guerin and Eisha Maharasingam-Shah “measuring the scale of online abuse targeting a variety of Congressional candidates in the 2020 US election.”

Women were far more likely than men to be abused on Twitter, with abusive messages making up more than 15% of the messages directed at every female1 candidate analysed, compared with around 5–10% for male candidates.

Women of ethnic minority backgrounds were particularly likely to face online abuse.

(M)ale politicians of ethnic minority backgrounds did not appear more vulnerable to abuse than their white counterparts.

Mitch McConnell received the most abuse of all male candidates both on Twitter and Facebook, with levels approaching or sometimes higher than female counterparts.

Both on Twitter and Facebook, abuse targeting women was more likely to be related to their gender than that directed at men.

Tommy Shane, in FirstDraft, about the questions we should ask before the next pandemic.

A study by academics and researchers at the University of Sydney “sampled 53 188 US Twitter users and examined who they follow and retweet across 21 million vaccine-related tweets (January 12, 2017–December 3, 2019). ” They concluded that a small percentage vaccine-critical (antivax?) information reaches Twitter users in the U.S. through bots. Is there a magic number? It’s not that simple, as Adam Dunn (one of the researchers) writes in The Conversation.