Of Committee Reports, Dangerous Algorithms and Benefits(?) of DCNs 🤯

The Information Ecologist 54

What is this? Surprise, surprise. This publication no longer goes by the name MisDisMal-Information. After 52 editions (and the 52nd edition, which was centred around the theme of expanding beyond the true/false frame), it felt like it was time the name reflected that vision, too.

The Information Ecologist (About page) will try to explore the dynamics of the Information Ecosystem (mainly) from the perspective of Technology Policy in India (but not always). It will look at topics and themes such as misinformation, disinformation, performative politics, professional incentives, speech and more.

Welcome to The Information Ecologist 54

Yes, I’ve addressed this image in the new about page.

In this edition:

What the IT Committee reports on Internet Shutdowns and Ethical Standards in Media Coverage said about misinformation and ‘fake news’.

A U.S. Senate hearing on ‘dangerous algorithms’, where written testimonies included references to India. One was also a good explainer for anyone trying to understand discourse around algorithms.

Can Digital Communication Networks enable benefits?

Committee Reports

On 1st December, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Communications and Information Technology published 2 reports:

Both reports reference misinformation/ ‘fake news’.

Report on Internet Shutdowns

The report on Internet Shutdowns does so in the recommendations, where it actually advocates for ‘banning of selective services, such as Facebook, Whatsapp, Telegram, etc.’🤯

Incidentally, this was the last recommendation - a memorable parting shot. I nearly fell off my chair.

The Committee feel that it will be of great relief if the Department can explore the option of banning of selective services, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Telegram, etc. instead of banning the internet as a whole. This will allow financial services, health, education and various other services to continue to operate for business as usual thereby minimizing inconvenience and suffering to the general public and also help in controlling spreading of misinformation during unrest. Adoption of such less restrictive mechanisms will be a welcome initiative.

The Committee strongly recommend that the Department urgently examine the recommendation of TRAI and come out with a policy which will enable the selective banning of OTT services with suitable technological intervention, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Telegram services during period of unrest/crisis that are liable to be used by the terrorists or anti- national element/forces to ferment trouble in the specified regions. The Committee look forward to positive development in this regard.

And, while I understand where the committee may be coming from in terms of attempting to narrow the disruption and prevent certain types of services from being blocked - this recommendation fails to recognise at least 3 things-

a) How the internet works: Such measures can be bypassed, but they also exacerbate inequity because not everyone will know how to.

b) How people respond to such measures: People who can, will migrate to other platforms. I shudder to think of the impact of serially escalating games of block-a-mole for most people.

c) How many people rely on Digital Communication Networks: We can argue that it isn’t ideal for so many people to depend on a small number of platforms/services, but the Facebook outage in early October affected many millions of Indians. [Indian Express] [Rest of World]

Aside: I had many more issues with the report, which I discussed with my colleagues in a forthcoming episode of All Things Policy (the episode will go up on 14th December, but I don’t have a link at the time of writing this).

Report on Ethical Standards on Media Coverage

This one clearly preferred the term ‘fake news (used ~35 times) over misinformation (used 4 times), but that’s not the bad part.

Let me quote from a summary by Sarvesh Mathi for Medianama.

Need more Fact Check Units (FCU): While appreciating the Press India Bureau (PIB) for setting up Fact Check Units in 17 Regional Offices of PIB, the Committee desired that MIB should open more such FCUs to remain vigilant for viral videos and news which might create public disorder.

Term “Fake News” should be broadly defined: The Committee also recommended that the term “Fake News” should be more broadly defined.

Regulatory mechanisms should embrace technology like AI to tackle fake news: Endorsing the view of Prasar Bharati CEO, the Committee recommended that regulatory mechanisms should look at embracing the latest technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) to check fake news and to be able to intervene in near real-time.

Legal provisions should be developed: The Committee noted that countries like Australia, Malaysia, and other democracies have anti-fake news laws and that the government should study their laws and develop legal provisions for India too.

Seek the expertise of non-government agencies: Naming AltNews, check4spam, and SMHoaxslayer, the Committee recommended that the government should factor in the expertise of these non-government agencies in the domain of fact-checking.

I want to focus on 2, 3 and 4.

Broad definition of ‘Fake News’

In this context, while appreciating the establishment of Fact Check Units in 17 Regional Offices of PIB, the Committee desires that the Ministry should open more such FCUs to remain vigilant for viral videos/news which should create public disorder. The Committee would also recommend that the term “Fake News” should be broadly defined.

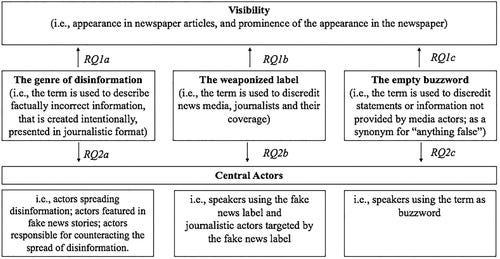

I must admit, I am really confused by what this is supposed to be mean. If anything, the problem with the term ‘fake news’ is that it is too broad, and in many situations, meaningless and unhelpful (See 52, which included this chart from a paper it cited).

A March 2020 paper, looking into the normalisation of the term ‘fake news’ in news coverage (in Austria) proposed three models - the genre, the label, the buzzword. [Journalism Studies - Volume 21, 2020 - Issue 10].

Using Artificial Intelligence

Again, the context in which it is referenced in the report isn’t particularly informative and does not mention how/what/when/where these methods may be deployed to mitigate the effects of misinformation and disinformation. I’m not saying it cannot be done, but a report of this magnitude should not uncritically cite such recommendations without further consultation. Plenty of reportage exists to show that automated systems also tend to get a lot wrong, or how codifying such recommendations in law can entrench the existing dominant market participants.

Legal Provisions

This one was an almost throwaway line in recommendation 21. And once again, I was off my chair (Ok, I lied, I didn’t really fall).

21. The Committee endorse the views of the CEO, Prasar Bharati that the regulatory mechanisms should look at embracing latest technologies such as Artificial Intelligence to check fake news and to be able to intervene in near real time. Hence, there is a need to take suitable steps accordingly and also to factor in the existing expertise in the domain of news fact check through non-Government agencies such as 'AltNews', 'check4spam', 'SMHoaxslayer' etc. Further, while observing that countries like Australia, Malaysia and other democracies have Anti- Fake News Laws, the Committee would like the Ministry to study their laws and develop some legal provisions to counter as big a challenge as fake news.

Earlier in the report, Russia, Australia and Malaysia were cited after paragraph 101.

101. When asked for details of the countries which have enacted legislation for tackling ‘Fake news’ along with their effectiveness, the Ministry have stated that as per Press Information Bureau, they have not conducted any exhaustive study of anti-fake news laws in other countries. However, the data gathered from public domain is as given below:

Now, I am not sure we want Russia as a role model in this regard. The Malaysian law it references was repealed in 2018. The report does point this out but did not seem to mention that a version of it came back as an ordinance earlier this year [Verfassungsblog]. Note, I am not implying mal-intent here. I am incredibly disappointed at the shallowness of the research.

When COVID-19 started spreading in Asia in the month before, Muhyiddin, then Minister of Home Affairs, stated that there were enough laws to curb fake news without AFNA. However, he changed his mind a year later. In January 2021, the Malaysian King issued a Proclamation of Emergency on request of the government that aimed to better contain the ongoing COVID-19 spread. Parliament was suspended. On 11 March 2021, the Emergency (Essential Powers) (No. 2) Ordinance 2021 was promulgated on the basis of Article 150 (2B) of the Federal Constitution which allows the promulgation of ordinances in circumstances that require immediate action.

While Australia does have a voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation (adopted by Adobe, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Redbubble, TikTok and Twitter), it does not appear to have a ‘fake news’ law along the lines of Singapore, etc. The law about ‘abhorrent violent material’ that the report references deals with broadcasting violent content and not false content/disinformation.

These inaccuracies aside, the question remains, does India need such legal provisions? No.

Well, these laws tend to be used against citizens, journalists and political opponents [The Economist]. Singapore’s first use of POFMA was against an opposition politician [ZDNet]. Edition 19: Of the states and state of information disorder plotted state responses based on whether they were supply-side/demand-side, mandatory/voluntary and aimed as governments, markets, societies and individuals (as you can see, the busiest quadrant is the mandatory/supply-side one. Multiple previous editions have also documented arrests/FIRs periodically. [Custom Google Search]

In the context of Kerala’s (ultimately withdrawn ordinance amending the Kerala Police Act to include a provision for a 3-year jail term for ‘intentionally and falsely defaming a person or a group of people’, I had written [Deccan Herald]

Across the country, there have been measures such as banning social media news platforms, notifications/warnings to WhatsApp admins, a PIL seeking Aadhaar linking to social media accounts, as well as recommendations to the Union Home Minister for ‘real-time social media monitoring’. Arrests/FIRs against journalists and private citizens for ‘fake news’ and ‘rumour-mongering’ have taken place in several states.

The 2020 Crime In India report (page 56) published by the NCRB listed a total of 1527 cases under the head “Circulate False/Fake News/Rumours (Sec.505 IPC/Sec.505 r/w IT Act)”. Also, note that due to the ‘Principal Offence Rule’, which considers only the ‘most heinous crime,’ i.e. with maximum punishment, as the counting unit - the number of cases are likely undercounted. My observation from a limited tracking of these cases is that they tend to be accompanied by more serious offences under 124 and 153 (I do not have data to back this up).

[Aside: These provisions did not seem to find even a mention in the IT Committee’s report - unless ctrl/cmd+F has failed me. Maybe that was because the report dealt primarily with media coverage. But the recommendations do not seem to be limited to the media - so why should any analysis of existing legal provisions be similarly constrained?]

I also happen to have a Google Alert set up that monitors reports of arrests/FIRs/cases being registered for false information on social media (here’s a link to the RSS feed if you’re interested). It generates ~2000 articles/month. Note: There are obviously many duplicates. I am not implying that there are ~2000 unique reports and/or cases a month.

All of this is to say is that we’re already (selectively) taking a lot of action based on what someone perceives to be false information, inappropriate comments through social media posts. We shouldn’t be too eager to go down the road of exploring blunt legislative instruments that are going shift the power dynamic further away from societies. At the very least, we should study existing laws and jurisprudence on the ‘prosecution of a lie’ first before we contemplate isomorphic mimicry. Ideally, this should be the Ministry of Law and Justice’s job.

Ad break (no private information was used in targeting this ad)You can find out more here.

And since we’re past 4th December, the early bird discounts no longer apply. Sorry about that.

A hearing about ‘Disrupting Dangerous Algorithms’

On 9th December, the U.S Senate Commission of Commerce, Science and Transportation held a hearing titled “Disrupting Dangerous Algorithms: Addressing the Harms of Persuasive Technology.”

Conversations around ‘algorithmic amplification have escalated ever since the Facebook Files/Papers/Documents reportage (Aside: Katie Harbath, formerly a public policy director at Facebook, compiled a lot of these till 11th November on a Google Doc). I am generally on the fence about watching these hearings. Torn between FOMO and, as I wrote in Prevalence, Performance and Politics - the performative dynamics involved in these hearings, which tend to diminish their utility more often than not. [SochMuch] (emphasis added)

… This may explain why videos containing bigotry and hate crimes are willingly circulated, or why birthday wishes are a Twitter affair, or why it seems like political leaders are on the hunt for that 2 minute video they can upload to YouTube and share on Twitter and Facebook, or why the Finance Minster quote tweets and tags a Board Chairman instead of a direct call (which may also have happened), or why politicians dunk on each other on Twitter, or why so many letters…

First, let’s get the references to India out of the way. 2 of the 4 written testimonies mentioned India.

Dean Eckles: Referring to the Trend Alert paper about cross-platform coordination to make political hashtags trend on Twitter (Also see 53: Participatory Dysfunction). As qualitative evidence of harm in non-algorithmic platforms (Whatsapp-related lynching). Both of these are on page 9.

Rose Jackson: In the context of the 2021 Intermediary Guidelines and similarity to legislation in Russia.

India, once a leader in democratic online governance, has recently implemented draconian rules that require platforms to take down content when requested by a government ministry, and to assign in- country staff dedicated to respond to these requests who are personally criminally liable if their companies refuse to do so. This Indian law in particular is reminiscent of provisions recently leveraged in Russia threatening Google and Apple’s in-country staff to compel the companies to remove an opposition party app from their platforms.

Now, I want to go back to Dean Eckles’s testimony because it also serves as a very useful explainer and also highlights the complexities (without actually confusing you).

I’ll cover some key points here, but as always, I recommend going to the source (linked earlier).

Scoring

In order to rank items in a newsfeed, platforms rely on a composite score which is a combination of the probability of a number of actions that a user may take (essentially a prediction that they may like, comment, (hit the bell icon?), hide, unfollow, etc.). [middle column in the image]

This prediction itself is based on a statistical analysis of the user’s history with the poster/certain types of content/kinds or content of images/tendency to interact/. ‘Latent position’ seems to refer to inferred preferences based on a user’s interaction and connections but haven’t been observed.

Actions taken by a viewer (liking a post, etc.) have implications for other users as well (the poster, in this case) and is something platforms try to account for as well.

How are weights assigned?

In some cases these weights may be selected through managerial judgement alone, but often sophisticated A/B tests are used to compare how different choices of weights affect metrics

The ranking may need to be done in sets:

When deciding what item to show in the second position, it can be useful to account for what the first item is; more generally, it can make sense to consider the full ranked set of items so as to reflect, e.g., demand for variety of topics or sources.

While public discourse tends to focus on feed algorithms, algorithmic ranking and selection play a role in other parts of the service too (friend suggestions, notifications, personalised search, etc).

Public discourse often has in mind a single feed (e.g., Facebook News Feed, TikTok’s series of videos), but these same items might be delivered to users via multiple feeds† and via email or mobile push notifica- tions, with these likewise subject to optimization. Established platforms are often ranking and recommending many types of items in many different formats. For example, many platforms suggest accounts to follow or friend based on numerous signals and with the aim of getting new users to make, e.g., engaging and var- ied connections.Many platforms also have personalized search functionality in many places, including some that might seem mun- dane or invisible (e.g., autocompletion of friends’ names when tag- ging them in photos).

Audits

I found this bit particularly interesting. Dean Eckles lists 3 ways that we can learn about their effects, along with the associated challenges. And also addresses relevant aspects of the ‘reverse-chronological’ v/s ‘algorithmically-selected’ debate.

Querying the algorithm with different inputs: See how an algorithm ranks different items—varying their characteristics and observing the difference(s) in outputs. A potential challenge is that researchers may not have access to large datasets of systematically varied inputs, as well as the different kinds of signals that a platform’s internal systems may use.

Comparing outputs across different algorithms for the same set of inputs: An example of this is a comparison between algorithmic and reverse-chronological feeds (see 43: Algo-read-ems). But there’s a cautionary note that this does not answer the ‘algorithmic amplification’ question.

While these kinds of comparisons are an important tool, they typ-

ically do not tell us about “algorithmic amplification” writ large. These comparisons tell us about how items would be ranked if — for a moment and for one account only — the algorithm was changed; they do not typ- ically tell us about what would happen if the algorithm were changed for a longer period of time and for many people or everyone.

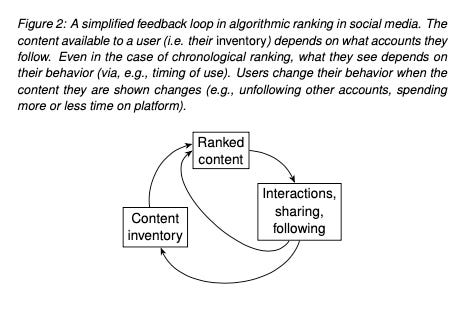

The feedback loop below represents the ways in which user behaviour affects what users may see, irrespective of whether a feed is reverse-chronological or not.

Using randomised trials. Here too, the question of reverse-chronological vs algorithmic feeds is taken up, with a reference to the Twitter study I wrote about in the last edition (See 53: Right to Amplify). Even though the study found that political content on the right tended to be amplified more, it does not answer the question of what happens when everyone is on a time-based feed. Also, pointed out is the possibility that if this were to happen, it is likely that users may respond in unpredictable ways. And that, this is a non-trivial task.

Platforms clearly regard these feedback loops, spillovers across users, and adaptive, strategic behaviors as important, with several industry and industry–academic teams working on methods to better quantify these effects. Thus, assessing what a ranking algorithm is amplifying is not a trivial task that platforms have simply neglected.

Related #1: Ada Lovelace Institute published a document about inspecting algorithmic systems. They list 6 methods:

Code Audits

User Survey

Scraping Audits

API Audits

Sock-puppet Audits

Crowd-sourced Audits.

Related #2: See Jonathan Stray’s thread on amplification

Benefits from Digital Communication Networks(?)

What! Prateek, did you just talk about benefits and social media platforms in the same heading?

Haha, Yes, I did. Hear me out. What a lot of you may not know is that as part of my regular day job at Takshashila Institution, I am part of a team that’s trying to figure out what we should do about them. Should we shut them down? Ignore the problems? Or find a path somewhere in between (obvious, no?). But is there really a way to <do not roll your eyes> minimise the harms and maximise the benefits? It would be so much easier if the changes to the scale and structure of human networks, the potential for virality of information, and algorithmic content selection (see 45: Crisis Disciplines, where I wrote about the important paper that highlighted these) were unequivocally bad.

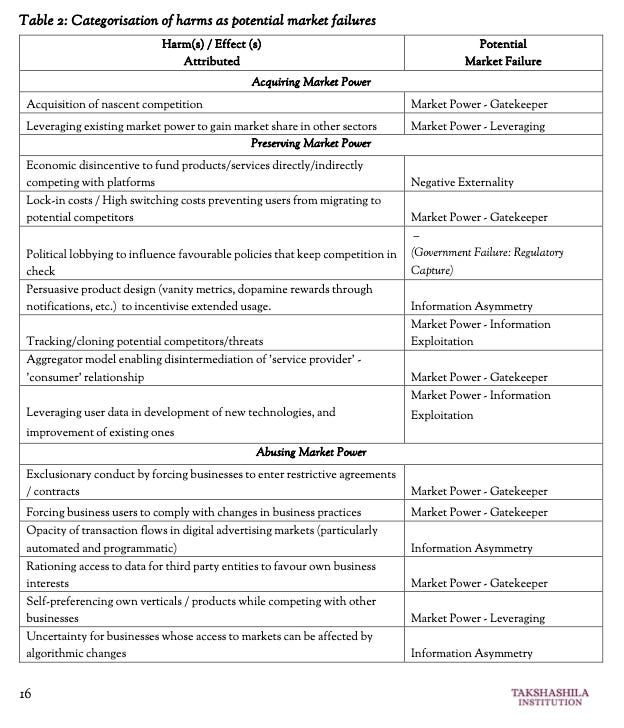

Back in July, we had published a paper categorising the various kinds of harms attributed to Digital Communication Networks as potential market failures, social problems and cognitive biases. I’m including some screenshots from the tables just to give you a sense of it - for the complete tables, do look at the original document.

But, in the course of writing that paper and a bunch of discussions during and after it on whether benefits are self-evident or not - we also realised that much of the analysis around the benefits/opportunities hadn’t really evolved much since the early/mid-2010s. Maybe we were just looking at the wrong sources… but what we found were either variations of the ‘Democratising Force’/Arab Spring angle or very specific and narrow use-cases.

So we signed off saying:

In subsequent work, we plan to identify the benefits that DCNs enable, assess overlaps and contradictions between proposed/enacted DCN governance measures, and explore the role of global internet governance mechanisms with the aim to define appropriate frameworks to govern DCNs.

This was back in July, mind you, long before the Facebook Files/Papers/Documents sent our heads spinning. Nevertheless, as Dean Eckles points out in his testimony discussed in the previous section (on Pages 1 and 5), or as Rebekah Tromble said in this episode of the TechPolicy.Press podcast, or as Rebeca Mackinnon noted in this episode 2 of the Internet of Humans podcast - we don’t have a grasp on the benefits.

So, in a forthcoming paper, we try to list out potential opportunities and benefits in the context of markets and societies. In this section, I’ll write a bit about how we approached their role in the benefits to societies section of the document.

One of the things we did in the harms paper was to define the concept of Digital Communication Networks (DCNs).

DCNs as composite entities consisting of:

Capability: Internet-based products/services that enable instantaneous low-cost or free communication across geographic, social, and cultural boundaries. This communication may be private (1:1), limited (1:n, e.g. messaging groups), or broad (Twitter feeds, Facebook pages, YouTube videos, live streaming), and so on.

Operator(s): Firms/groups that design/operate these products and services.

Networks: The entities/groups/individuals that adopt/use these products and services, and their interactions with each other.

And while the term may not ever catch on, we didn’t just make it up for the heck of it 😜.

The purpose of introducing a new frame is to encourage the study of DCNs from the perspective of their effects on societies as a whole rather than a specific focus on a specific set of firms, technologies, sharing mechanisms, user dynamics, and so on.

In the context of societies, we tried to focus on the role of capabilities and networks, and not the firms themselves - though, it isn’t possible to always ignore them.

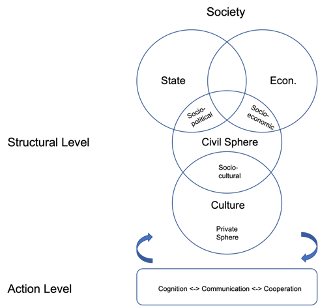

First, we had to try and visualise what societies look like. When attempting something like this, there will always be layers of abstraction - and no model (no matter how good) can perfectly capture systems as complex as modern societies. Nevertheless, we found that the model that Christian Fuchs and Daniel Trottier propose in Social Media, Politics and the State could be a useful one. Some key points from it:

It contains the following subsystems: overlapping state and economic spheres, a cultural sphere, and a civil sphere that mediates the cultural and overlapping state and economic spheres.

The civil sphere is composed of socio-political, socio-economic, and socio-cultural movements.

These movements are struggles for different ends by various social roles within the subsystems.

The Movements are:

Socio-political: For the “recognition of collective identities via demands on the state.”

Socio-economic: For the “production and distribution of material resources created and distributed in the economic system.”

Socio-cultural: Have “shared interests and practices relat[ed] to ways of organising one’s private life.”

The Roles:

Trottier and Fuchs use the tripleC framework to explain that DCNs allow actors to perform tasks of creation (cognition), share them others who can respond (communication), and modify them (cooperation) in an integrated manner, and that they can all occur in the same social space (capability built by DCN operators).

Building on this, we identify 5 types of actions that DCNs enable. Note that these are not mutually exclusive. And, in most cases, they overlap. We had to use a non-exhaustive set of examples in the paper to show where DCNs played a role in minimising harms or enabling benefits through a combination of one or more of these actions.

Information Production/Consumption: Low entry costs and capabilities for users to generate and share content enable participation in DCN Networks at scale. Under this action, we refer narrowly to the ability to transmit information or receive information.

Interaction: Interaction involves receiving and then responding to information. This can manifest itself in various ways. It can mean mutual communication between two or more actors belonging to any of the societal subsystems identified earlier. This communication can also be directed at a completely different set of actors and may or may not include the original set of actors. Responses need not be limited to communication / sharing on DCN networks but can also include actions taken off them such as physical actions, internalising information or any of the 5 kinds of actions identified in this section.

Identity Formation/Expression: Identity formation and expression are complex processes. User profile-centric DCN services provide a natural home for the performance of identity, which itself can lead to the accumulation of social capital. Identities also evolve as actors across the subsystems consume information, interact with information and other actors across DCN networks. These identities (individual or collective) may then be further expressed using DCN capabilities and features.

Organisation: A combination of DCN capabilities and networks reduces barriers for groups of people to cooperate and act towards achieving common or similar goals. They can also aid the scaling phase of self-organising or spontaneous movements. It should be noted that the mere existence of DCN capabilities and networks is not sufficient. The networks also need to include motivated actors with incentives to do so.

Financial Transactions: In this context, we refer to transactions where DCNs play a connective role, and not where the DCN operators are themselves a party to the financial transaction (ad revenue sharing, creator pay-outs, create their own tokens, news partnerships, funds for research and civil society organisations, and so on).

I don’t have a link yet but will include one in the edition right after it gets published.

In the meanwhile, if you want to talk to me about it / see a draft - you can reach out via Twitter DMs (@prateekwaghre) or email me (<FirstName> AT takshashila.org.in)

Sorry, this edition turned out to be a lot longer than I had planned. Here’s an animal gif to make up for it.