Of crisis disciplines, breaking and fixing algorithms and democracies

MisDisMal-Information Edition 45

What is this? MisDisMal-Information (Misinformation, Disinformation and Malinformation) aims to track information disorder and the information ecosystem largely from an Indian perspective. It will also look at some global campaigns and research.

What this is not? A fact-check newsletter. There are organisations like Altnews, Boomlive, etc., who already do some great work. It may feature some of their fact-checks periodically.

Welcome to Edition 45 of MisDisMal-Information

In this edition

The impact of digital communication networks on collective behaviour as a ‘crisis discipline’.

The idea of ruining and fixing personal algorithms.

Exporting political values

… Meanwhile, in India: 1 year of the ‘Tiktok ban’, Rainy and Son(y) days for Twitter, hate on clubhouse

Collective behaviour as a crisis discipline…

17 researchers came together to make the case that the study of collective behaviour must rise to a “crisis discipline”:

Over the past few decades “collective behavior” has matured from a description of phenomena to a framework for understanding the mechanisms by which collective action emerges (3–7). It reveals how large-scale “higher-order” properties of the collec- tives feed back to influence individual behavior, which in turn can influence the behavior of the collective, and so on

Carl Bergstrom’s thread adds a lot of perspective 👇

They identify 4 characteristics of this interaction of communication technology and global collective behaviour.

Increased scale of human social networks

Changes in network structure

Information fidelity

Algorithmic Feedback

So, why a crisis discipline?

Ok, Prateek, why are you throwing a tweet thread at me?

Well, because this matters immensely from a public policy perspective. Regulatory momentum around the world is picking up. And with an incomplete understanding, there’s a good chance we’ll aim some of our interventions at the wrong thing(s).

Fixing and breaking ‘my algorithm’

In 42 (Of Algo-Read'ems, (Col)Lapses in Time, Moderating Moderation), I wrote about a study that attempted to quantitatively analyse the difference between Twitter’s algorithmic and reverse-chronological feed. And if you go back and read Nicholas Negroponte speculative opening of ‘the Daily Me’, he concludes (emphasis mine):

The market for news, entertainment, and information has finally been perfected. Consumers are able to see exactly what they want. When the power to filter is unlimited, people can decide, in advance and with perfect accuracy, what they will and will not encounter. They can design something very much like a communications universe of their own choosing.

This bit reminded me of a fascinating piece I came across this week about TikTok’s recommendation algorithm [Kaitlyn Tiffany - The Atlantic]. It is based on the premise that TikTok’s supposedly accurate algorithm tended to recommend ‘disgusting’ videos to the author. But the part that struck me was where she detailed the relationship between an individual and ‘their algorithm’.

This is disturbing because the recommendation algorithm that TikTok uses to pull videos for the personalized “For You” feed is known for being scarily precise, to the point where intelligent people have expressed concern that it might be used for mind control. TikTok users often refer to the process that produces the feed in front of them as “my” algorithm, as if it really were an extension of self.

And the idea that people can ‘fix’ and ‘ruin’ their ‘personal algorithms’.

When people complain that they’ve somehow “ruined” their personal algorithm, they probably know exactly what they’ve done. We are all working so hard every day at destroying one another’s brains.

Combined with the age-old idea that algorithms optimise for engagement (irrespective of type) and (as of now), there few incentives to change (though the political economy around that certainly seems to be shifting)

There might be a way for TikTok to differentiate between sincere engagement and horrified engagement, McAuley said, but it wouldn’t be as useful for the company as it would be for me. “Why would they want to solve those problems?” he asked.

This is even more relevant in the case of ‘atomised content’ feeds like TikTok, where the virality of a single piece of content is less affected by the network structure and relative position of the content poster, as compared to other social networks.

Yes, Yes, I know TikTok is banned in India (see Meanwhile, in India section). But its success and the stress on its algorithm as a differentiator means it extends beyond just one platform.

Fixing and breaking democracy

The internet promised to help information flow around the world. But social media and their algorithms have just amplified America’s voice.

This was the concluding line in a recent Economist article about the role of social media in accelerating the export of America’s political culture.

Consider the Black Lives Matter (blm) protests which erupted in America in 2020. They inspired local versions everywhere from South Korea, where there are very few people of African descent, to Nigeria, where there are very few people who are not. In Britain, where the police typically do not carry firearms, one protester held aloft a sign that read, “demilitarise the police”

This, of course, could work for other things like QAnon and ‘Stop the Steal’:

Back in May, Priyam Nayak, Joe Ondrak, Ishaana Aiyanna and Ilma Hasan noticed allegations about ‘stolen’ elections in West Bengal [Logically].

Anne Applebaum cites recent examples for Israel and Peru and potential groundwork in Brazil and Hungary [TheAtlantic]. On the question of why democracies are so vulnerable (especially those unfamiliar with such tactics), she writes:

the primary danger of “Stop the Steal” tactics lies precisely in their novelty: If you haven’t seen or experienced this kind of assault on the fundamental basis of democracy—if you’ve never encountered a politician who is actively seeking to undermine your trust in the electoral system, your belief that votes are counted correctly, your faith that your nation can survive a victory by the other side—then you might not recognize the hazard.

Mark Scott writes about election fraud claims in Germany as it heads into elections in September [Politico] - based on an ISD Global Report.

And antivax narratives.

A recent FirstDraft analysis of Antivax narratives in West Africa identified multiple narratives and messages originating in the US and Europe that found their way to West Africa.

… Meanwhile, in India

▶️ 29th June will mark a year since the ‘TikTok ban’ (yes, there were 58 other apps too). I know what some of you were thinking. It can be circumvented by using VPNs. Calling this ‘Porous Censorship’, Margaret E. Roberts writes in Censored

Porous censorship is useful … precisely because only some individuals circumvent it.

…

Porous censorship, on the other hand, frustrates the vast majority of citizens from accessing information the government deems dangerous, while not making any information explicitly off-limits and allowing online consumers to feel as if all information is possible to access.

▶️ For Twitter, when it rains, it pours. Even the son(y) doesn’t help

The one year mark is significant given the tussle between the Union Government and Twitter that has dominated headlines for the better part of the year, even with a pandemic raging. Many are trying to guess if/when Twitter will be blocked in the country.

And this was perfect timing for an overzealous DMCA notice by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) on behalf of Sony Music, leading to Union Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad’s Twitter account being locked for an hour [Hindustan Times]. It was spun as targeted action against the minister - when occurrences such as this from overzealous DMCA enforcement are as old as the DMCA itself. EFF documented many of these in its Unintended Consequences Archive. Why? Because when there’s a threat of coercive action, platforms will lean towards over-moderating. This is precisely the argument against automated content takedowns in other contexts.

▶️ No resp(IT)e Rules

Not a great week for the IT Rules.

The UN Special Rapporteurs on (I’ve shortened the official designations) freedom of opinion and expression, freedom of peaceful assembly, and privacy express their concerns about the rules [pdf].

Incidentally, they mentioned the farmer protests, which were also cited in a Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression [pdf], in the context of political pressure on platforms.

13 media houses have challenged the rules in court [Sanyukta Dharmadhikari - TheNewsMinute]

Thirteen media outlets in India under the Digital News Publishers Association (DNPA) have moved the Madras High Court against the new IT Rules, asking that the court declare the new Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 as ultra vires, void and violative of fundamental rights under the Constitution.

▶️ In the club(house)

You can probably guess my age based on that sub-head.

Some coverage this week about hate speech on Clubhouse in India. Of course, in some shape or form, these concerns have been around since September 2020 [TheVerge]. And, you could have seen this coming. But here’s a quick round-up.

Islamophobia to Casteism, How Hate Thrives Unchecked on Clubhouse [Asmita Nandy - TheQuint]

Inside the Islamophobic Clubhouse Rooms Modi’s Men Visit [Yashraj Sharma - Vice]

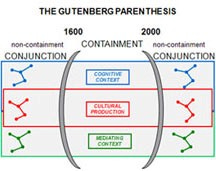

It is also worth noting how this audio format (live and on-demand - podcasts) draws us further away from the Gutenberg Parenthesis.

▶️ Bye, bye hate speech?

3 channels were fined for their coverage of Tablighi Jamaat last year.

Will this mean an overnight change? No. But this is still significant.