Of it's (not just) the false information, stupid

What is this? MisDisMal-Information (Misinformation, Disinformation and Malinformation) aims to track information disorder and the information ecosystem largely from an Indian perspective. It will also look at some global campaigns and research.

What this is not? A fact-check newsletter, in fact, it isn’t even really a ‘news’letter. It may, however, sometimes include some examples of fact-checking taken up by some of the organisations who find themselves dealing with misleading information every day.

Welcome to Edition 52 of MisDisMal-Information

In this edition:

It’s (not just) the false information, stupid: Growing consensus that we’re devoting too much effort to mis/disinformation, terms that are meeting the same fate as ‘fake news’

A follow-up on what the documents leaked by Frances Haugen say about India.

Update 2021-10-12:

The email version went out with placeholder text under ‘In this edition.’ Added for the web version.

Corrected some text towards the end of the first section - “all these concerns translate into two significant concerns” replaced with “all of this translates into …”

It’s (not just) the false information, stupid

A few months ago, here is what Vishal Ramprasad and I wrote in the discussion section of our paper attempting to categorise the harms attributed to Digital Communication Networks (DCNs) (emphasis added):

For narratives, the majority of the harms were amplified by the scaling effects of DCNs. The combination of incentives to ‘perform and participate’ in attention markets, affordances for control and manipulation of information, result in the lowering of trust in institutions and news media, leading to a negative impact on social cohesion. This resonates with the higher occurrences of cognitive biases associated with tribalism (anchoring, stereotyping, bandwagon), and the recency/availability of information based on our classification. The implications for public discourse and information ecosystems extend beyond the consideration of just the truth and falsity of a particular message.

It wasn’t to downplay any of the issues associated with false/misleading content - but to ensure we are placing them at the appropriate level in the overall scheme of things. Is it a big problem? Yes. Is it the biggest problem we have? The answer is simple, no. It is one among many that we categorised. Its relative rank, on the other hand, is harder to state objectively. But that makes, not overstating it, all the more critical.

Samuel Woolley says this more explicitly in an article titled ‘It’s time to think beyond disinformation and false news’ [CIGI] (emphasis added):

Facebook, YouTube, WeChat, TikTok and many others aren’t simply facilitating — or failing to curb — the spread of harmful disinformation. Most social media platforms are crucibles for a wider range of nefarious and coercive communication, including coordinated propaganda, hate speech, state-sponsored trolling, sophisticated phishing campaigns and predatory advertisements. Organized crime groups and known terror organizations use them to communicate and organize.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t benefits to social media. Democratic activists in autocracies can leverage social media in their fights for freedom, and people use these platforms to keep in touch with friends and family. Instead, it’s to say that disinformation is one problem among many. Despite this, many researchers, policy makers, journalists and technology experts continue to focus overwhelmingly on the threat of false content over social media. The Wall Street Journal’s new series adds to a growing trove of research and reporting that points to much broader informational issues online.

And calls for expanding the frames we’re using:

Those working to study and address the communicative problems and the attendant socio-political fallout over social media must look beyond the problem of disinformation. It’s time for us to expand our frames for understanding the ongoing crisis with digital media to include broader issues of propaganda, coordinated hate, manipulative content about electoral processes, and incitement of violence. Often, the people and groups using social media as a mechanism for sowing such campaigns do not use disinformation or false news at all. In fact, the illegality of the content and intentions of its creators are frequently more clear-cut with these types of informational offensives.

Aside: Look, I get some of this sounds rich coming from a publication that calls itself MisDisMal-Information and focuses on Information Disorder. But if you go back over past editions, you will notice that the amount I focus specifically on just information disorder has reduced. This is, likely, in contrast with an increasing focus on the broader effects and implications for the Information Ecosystem. But I’ll admit, it wasn’t a quick, overnight switch that’s easy to spot. Instead, it was a gradual shift. Oddly, I have still retained the image that says ‘MisDisMal-Information, MisDisMal-Information everywhere…’ - perhaps it is time for a change.

He also notes two problems with this ‘myopic focus.’

The terms fake news, misinformation, and disinformation have more or less lost meaning since political leaders use them to stigmatise views/positions they disagree with. Note the politicals leaders referenced by name. But that’s a broader point for another edition.

This idea of these terms losing their meaning is something Renée DiResta notes in her essay, “It’s not misinformation. It’s just amplified propaganda”, too. But from the perspective of scope creep. [The Atlantic]

Confronted with campaigns to make certain ideas seem more widespread than they really are, many researchers and media commentators have taken to using labels such as “misinformation” and “disinformation.” But those terms have fallen victim to scope creep. They imply that a narrative or claim has deviated from a stable or canonical truth; whether Pelosi should go is simply a matter of opinion.

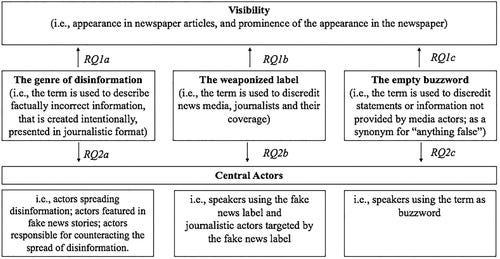

A March 2020 paper, looking into the normalisation of the term ‘fake news’ in news coverage (in Austria) proposed three models - the genre, the label, the buzzword. [Journalism Studies - Volume 21, 2020 - Issue 10].

I would subjectively argue that ‘misinformation’ and ‘disinformation’ have followed a similar path based on two things - the tendency of politicians/state authorities to dismiss opposition as misinformation or disinformation and use the specific terms as justification for various actions, and the increasing volume of articles that get caught on the various alerts I have set up for these terms.

The opportunity cost + knock-on effects of the ‘narrow focus’.

a narrow focus on disinformation stymies research on other issues and can lead to unintended consequences. Not only do researchers themselves focus less on other issues, such as hate speech, electoral tampering, or incitement to violence, but their focus on disinformation spurs others to act accordingly. Like a snowball gaining speed and bulk as it rolls downhill, our study of and concern with disinformation has developed its own momentum.

In the context of its critique as a field of study, it is worth going back to Joseph Bernstein’s essay from September [Harper’s Magazine]. You can ignore the context of ‘the commission’ as he stresses on the construct of ‘Big Disinfo’.

The Commission on Information Disorder is the latest (and most creepily named) addition to a new field of knowledge production that emerged during the Trump years at the juncture of media, academia, and policy research: Big Disinfo. A kind of EPA for content, it seeks to expose the spread of various sorts of “toxicity” on social-media platforms, the downstream effects of this spread, and the platforms’ clumsy, dishonest, and half-hearted attempts to halt it. As an environmental cleanup project, it presumes a harm model of content consumption. Just as, say, smoking causes cancer, consuming bad information must cause changes in belief or behavior that are bad, by some standard.

And it’s not just the professional incentives of researchers at play, as Mike Masnick points out in his take on Bernstein’s essay [TechDirt]:

An important (and often overlooked!) point that Bernstein makes in the piece is that the big internet companies were pretty quick to embrace this idea that "disinformation" is a problem. It is true that Mark Zuckerberg initially pushed back on the idea, but after basically everyone attacked him for that, he quickly began his apology tour. And, why not? Even as it makes the company look bad in the narrative, at its core, the idea that disinformation on Facebook impacted the American election can be spun to be positive for Facebook. After all, if Facebook is so powerful, shouldn't you be advertising on it, Mr. Toilet Paper maker? If Facebook can help get Trump elected because of some memes posted by idiots, just think how much beer and nachos it can sell as well? Literally, Facebook has a vested interest in having people believe that disinformation works on its platform, because that's literally something the company can profit from.

I share Bernstein’s concern of professional incentives, even if I don’t entirely agree with “all” aspects of his criticism (e.g. I do believe the ‘information ecosystem’ is a useful metaphor - It would be dishonest of me not to point out the potential role of my own professional incentives here).

In addition, I also come at it from a different perspective that many of the conversations are ‘stuck’ with various incidents/situations rhyming even, if not outright repeating. As I wrote in July [46 - Outrage against the machine, digital communication networks, link rot]:

Like many other fields, there is a lot of day-to-day activity (some of it is noise, some of it is useful), but the overall rate of change is pretty slow. So while I’ve spent countless hours figuring out who said what, who said what first, who responded, how sometimes I’ve felt I am making the same points over and over. Maybe that’s not a bad thing…

Perhaps, we need more data from firms operating DCNs, and maybe that will come from regulation (in some countries), as this proposal from Nathaniel Persilly argues for. Or perhaps, we need to go back and re-look at some of the literature on propaganda as this special edition of Misinformation Review suggested. Or perhaps, we need to turn to the cognitive sciences (some of this is already happening, but consensus is a slow-moving process). Most likely, we’ll need to do all of these and then some.

(This is not from Samuel Woolley’s article, but something I’ve added) As if all this wasn’t complex enough. The edition of Stratechery that I quoted in 51 - Reading between the lines of the facebook files teased the idea that, perhaps, all this focus on misinformation may actually be making the problem worse. While, he says so in the context of Facebook’s efforts to take action against false/misleading content, but if we accept his argument of ‘confirmation bias fodder’, then there’s reason to think that those dynamics occur outside Facebook too. Note, I do think this is distinct from the ‘backfire effect’ conversation, which focuses on the effects of information contrary to one’s assumptions/biases/worldview. In this case, it is to do with attempting to fact-check the unknown (notice the similarity with Renée DiResta’s observation about opinions) and its role in adding to outrage and polarising conversation/content.

Here’s the thing: of course facts have changed. We are in the middle of a pandemic from a novel coronavirus, bringing to bear vaccines based on a completely new technology. I would be far more concerned if facts were not changing than if they were.

That’s the problem, though: rules and regulations, particularly when applied at scale, by definition must be inflexible. Moreover, those rules and regulations, as applied by the tech companies, are downstream from regulators and politicians incentivized to be more cautious and controlling than not. This makes it inevitable that fact-checks are wrong, or behind the times, or subject to revision. The way this is experienced by end users, though, is not as an expression of epistemic doubt, but rather crude censorship.

If a case could be made that misinformation is a causal factor in bad outcomes — as opposed to being confirmation bias fodder that is leveraged to support a pre-existing point of view — then perhaps the ongoing risk of getting it wrong (continually) would be worth it.

…

… If you think that … <reference removed to simplify> … that contrarianism and political polarization are what actually matters — how does it help to be implementing a system of certainty on the shifting sands of evolving understanding? Doesn’t the inevitable “changing of facts” — justified though they may be — simply give ammunition to the already paranoid that no one knows anything, …

From an Indian perspective, all of this translates into two significant concerns from where I stand:

We have not studied this deeply enough in the Indian context. Nowhere close to it.

We are likely to moral panic ourselves into legislation (this may be a single new law, a set of new laws, updates to existing laws, or some combination) that feed into the label and buzzword aspects and result in the criminalisation of (inconvenient) information and speech.

Follow-up on Facebook Files and India

Shortly after I scheduled edition 51, CBS News published the whistleblower Frances Haugen’s complaint to the U.S. S.E.C. While most of the assumptions I made for India (based on existing patterns) hold, there’s still an additional level of detail worth looking into.

Anuj Srivas picked out the bits relevant to India [The Wire].

India is a Tier-0 country with the U.S. and Brazil:

This is good news, because Tier-2 and Tier-3 countries apparently at one point received no investment in terms of proactive monitoring and specific attention during their electoral periods.

On the other hand, this categorisation may not be as meaningful as it appears because a separate notation on “misinformation” implies that the US receives 87% of whatever resources are available, while the “rest of the world” receives just 13%.

Facebook is aware of “anti-Muslim content, and what it refers to as fear-mongering promoted by pro-RSS users or groups.” And the lack of classifiers in Hindi and Bengali means that a lot of this content is never flagged. It should be noted that is a cat-and-mouse situation because malign creativity implies that those posting such content are constantly evolving. The most unexpected example I’ve come across is the use of the names of 2 taxi aggregators in India in such a way that it represents an anti-minority slur.

Virality of Misinformation

The presence of Coordinated Authentic Actors or what Facebook now seems to call Coordinated Social Harm

Coordinated authentic actors seed and spread civic content to propagate political narratives…the message comes to dominate the ecosystem with over 35% of members having been recommended a cell group by our algorithms,” the document notes.

This should be an interesting space to watch considering that, in September, Facebook had announced its intention to take action against such Coordinated Social Harm.

Coordinated social harm campaigns typically involve networks of primarily authentic users who organize to systematically violate our policies to cause harm on or off our platform. We already remove violating content and accounts under our Community Standards, including for incitement to violence; bullying and harassment; or harmful health misinformation.

However, we recognize that, in some cases, these content violations are perpetrated by a tightly organized group, working together to amplify their members’ harmful behavior and repeatedly violate our content policies. In these cases, the potential for harm caused by the totality of the network’s activity far exceeds the impact of each individual post or account. To address these organized efforts more effectively, we’ve built enforcement protocols that enable us to take action against the core network of accounts, Pages and Groups engaged in this behavior. As part of this framework, we may take a range of actions, including reducing content reach and disabling accounts, Pages and Groups.

Again, we’re not sure how exactly this will be implemented. I wonder if we should expect different kinds of political mobilisation to get caught up in this because the mechanisms of amplification will remain similar whether the message is ‘harmful’ or ‘beneficial’. Besides, one can always claim to be harmed by any sort of political mobilisation. Will Facebook rely on user complaints? Will it identify them on its own?

Programming Note: I expect one of the editions in October to be delayed/interrupted due to some other work commitments + deadlines I have for the month. Unfortunately, I am not sure which one.