Of reading between the lines in the Facebook files, Rus(sia)hing to decisions

MisDisMal-Information Edition 51

What is this? MisDisMal-Information (Misinformation, Disinformation and Malinformation) aims to track information disorder and the information ecosystem largely from an Indian perspective. It will also look at some global campaigns and research.

What this is not? A fact-check newsletter. There are organisations like Altnews, Boomlive, etc., who already do some great work. It may feature some of their fact-checks periodically.

Welcome to Edition 51 of MisDisMal-Information

In this edition:

Reading between the lines of the Facebook files: A few themes that were interesting and/or under-explored.

Rus(sia)hing to decision-making: Recent events in Russia represent a microcosm of issues at the intersection of technology and geopolitics, let’s look at a few of them.

Reading between the lines of the Facebook Files

This is not an in-depth summary of all the possible aspects WSJ's reporting covered [Facebook Files]. Instead, I am picking a handful of themes that I thought were either interesting or didn't get enough attention.

What do the Files mean for India?

Spoiler alert: Not much (for now), and a lot.

In the eight articles currently filed as 'Facebook Files' on the WSJ's website, India is directly referenced just twice. And there were two additional sets of references in the internal reports published by the WSJ ahead of the Senate Commerce Committee hearing scheduled for this week. Note: I am not implying WSJ was obliged to centre any particular country in the way they've framed their story. It is also worth pointing that we don't know if all contents of the documents available to them have been reported on, so India-specific reportage could emerge in the future. It will be amazing if they publish something between the time I schedule this edition, and it hits your inbox.

But here's what we have so far.

The first, an almost throwaway reference in the 3rd story about changes to the newsfeed algorithm that seemed to incentivise angry exchanges (as per the frame of the story)

Facebook researchers wrote in their internal report that they heard similar complaints from parties in Taiwan and India.

The context was that political parties had learned that attacks on political opponents netted higher engagement.

An April 2019 document ‘Political Party Response to ‘18 Algorithm Change’ apparently stated:

Engagement on positive and policy posts has been severely reduced, leaving parties increasingly reliant on inflammatory posts and direct attacks on their competitors.

Poland:

“One party’s social media management team estimates that they have shifted the proportion of their posts from 50/50 positive/negative to 80% negative, explicitly as a function of the change to the algorithm,”

Spain:

The Facebook researchers, wrote in their report that in Spain, political parties run sophisticated operations to make Facebook posts travel as far and fast as possible.

“They have learnt that harsh attacks on their opponents net the highest engagement,” they wrote. “They claim that they ‘try not to,’ but ultimately ‘you use what works.’ ”

Central / Eastern Europe

(emphasis added)

Nina Jankowicz, who studies social media and democracy in Central and Eastern Europe as a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, said she has heard complaints from many political parties in that region that the algorithm change made direct communication with their supporters through Facebook pages more difficult. They now have an incentive, she said, to create posts that rack up comments and shares—often by tapping into anger—to get exposure in users’ feeds.

The second reference came in the very next article in the series, in the context of violent images:

India has more than 300 million Facebook users, the most of any country. Company researchers in 2019 set up a test account as a female Indian user and said they encountered a “nightmare” by merely following pages and groups recommended by Facebook’s algorithms.

“The test user’s News Feed has become a near constant barrage of polarizing nationalist content, misinformation, and violence and gore,” they wrote. The video service Facebook Watch “seems to recommend a bunch of softcore porn.”

After a suicide bombing killed dozens of Indian paramilitary officers, which India blamed on rival Pakistan, the account displayed drawings depicting beheadings and photos purporting to show a Muslim man’s severed torso. “I’ve seen more images of dead people in the past 3 weeks than I’ve seen in my entire life total,” one researcher wrote.

Aside: This 'test account' research methodology is something Facebook's Public Relations teams constantly dispute, so it was interesting to see it being deployed internally. To be fair, we don't know if the same concerns about the methodology were flagged about this report too

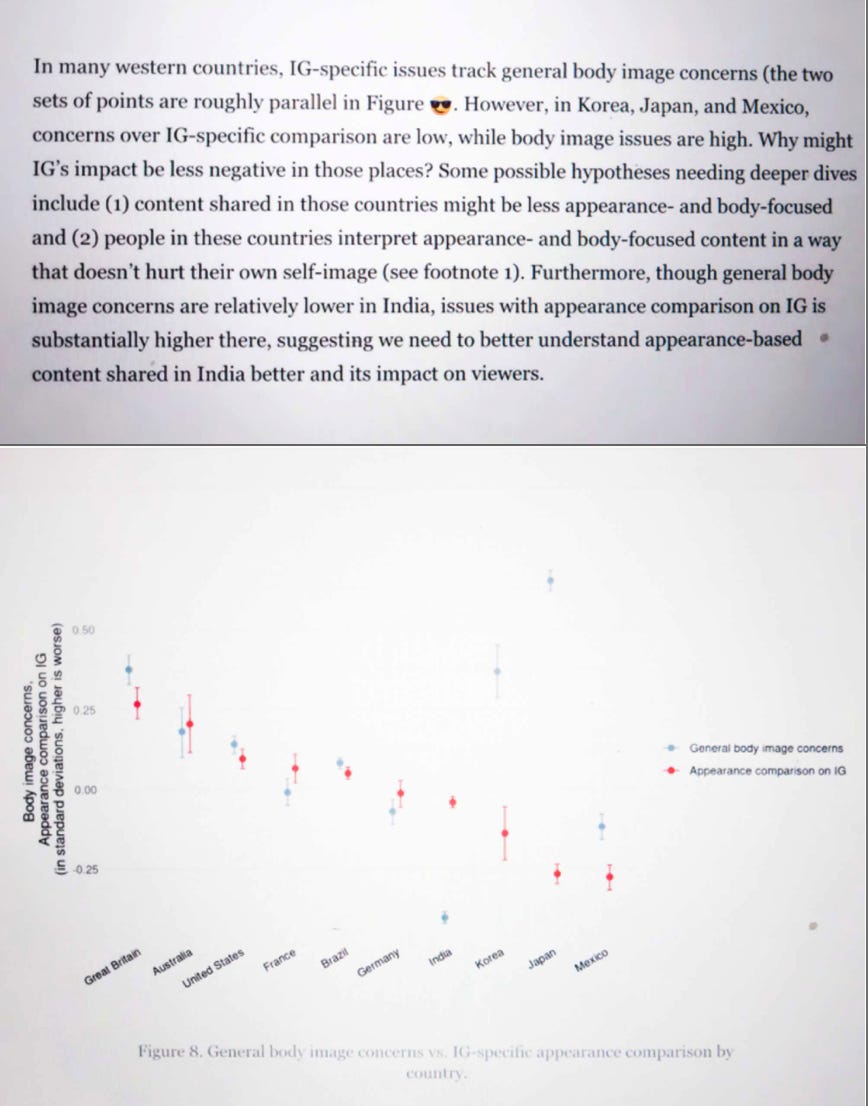

The third - buried in one of the reports about appearance-based social comparison on Instagram that WSJ published (from Feb 2021).

In most countries, it is worse among women. In India, comparison is higher among men than women.

The same report later referenced India, stating that though general body image concerns are low in India, "issues with appearance comparison on IG <sic> is substantially higher... suggesting the need to better understand appearance-based content shared in India and its impact on viewers":

The final set of references was in a report from Jan 2021. The first reference seems to show the same data as the chart on social comparison from Feb 2021 report, just shown in a different way.

The second, though, added a distinction between teens/non-teens.

And, while there weren't specific examples, many issues highlighted in the series were likely applicable here too. Though, they probably remain under-explored both inside and outside the company.

Differential enforcement of rules and opaque notifications" to "minimise conflict with average users."

An internal memo from June 2020 which recommended the separation of "content policy from public policy."

Time/resources dedicated to enforcement. There was an interesting stat comparing efforts dedicated to working on content from outside the U.S. versus content from the U.S. The article earlier pointed out that 90% Facebook's monthly users were outside U.S. and Canada

In 2020, Facebook employees and contractors spent more than 3.2 million hours searching out and labeling or, in some cases, taking down information the company concluded was false or misleading, the documents show. Only 13% of those hours were spent working on content from outside the U.S. The company spent almost three times as many hours outside the U.S. working on “brand safety,” such as making sure ads don’t appear alongside content advertisers may find objectionable.

Lack of capacity for vernacular languages.

Professional Incentives

In quotes about political parties in various countries, note the positioning of actors as involuntary participants - "We're only posting such content because it gets engagement!" (which is consistent with the preceding parts of the article that dealt with media organisations and their incentives).

One could argue that it is a choice not to post such content in the first place and take the proverbial high road. The issue there is, in an environment where no one wants to be the first to do that (because there is no guarantee that others will follow - likely making the first mover the first loser), what we get is a race to the bottom. If lemmings did indeed throw themselves off cliffs, metaphorically, this is what it would seem like, no?*

But really, this is a tale of professional incentives. Facebook and anyone posting on it will optimise for engagement. See this thread by Facebook's ex-Civic Integrity Lead 👇.

And despite a host of voices attributing it to ‘the advertising model', which incentivises engagement, the ad tech space remains heavily under-studied, as Shoshana Wodinsky points out in this exchange on CharWarzel'sel's Galaxy Brain newsletter.

Homework: Count, on your fingers, the number of industries that rely on prioritising engagement. It should take you no more than 3-5 minutes to run out of fingers.

The misinformation focus

Ben Thompson flags something significant about the effort comparison stat that I had completely missed. Those 3.2 million hours were for "information the company concluded was false or misleading".

He notes that the statistic:

doesn’t say anything about human trafficking or the other atrocities detailed in the story; the focus of all of those employees spending all of those hours is misinformation.

Hubris and Banality

A notable thread throughout the entire series is that researchers/employees Facebook had seemingly done the internal research, flagged concerns, thought of potential solutions only to be thwarted by its senior management.

As Mike Masnick observes:

The issues, which become clear in all of this reporting, are not of a company that is nefariously run by evil geniuses toying with people's minds (as some would have you believe). Nor is it incompetent buffoons careening human society into a ditch under a billboard screaming "MOAR ENGAGEMENT! MOAR CLICKS!" It seems pretty clear that they are decently smart, and decently competent people... who have ended up in an impossible situation and don't recognize that they can't solve it all alone.

In this post, he proposes a 'hubristic mentality' model:

Over and over again, this recognition seems to explain actions that might otherwise be incomprehensible. So many of the damning reports from the Facebook files could be evidence of evilness or incompetence -- or they could be evidence of a group of executives who are in way too deep, but believe that they really have a handle on things that they not only don't, but simply can't due to the nature of humanity itself.

...

As Will Oremus points out at the Washington Post, the real issue here is in the burying of the findings, not necessarily in the findings themselves.And, again viewed through the prism of a hubristic "we can fix this, because we're brilliant!" mentality, you can see how that happens. There's a correct realization that this report will look bad -- so it can't be talked about publicly, because Facebook seems to have an inferiority complex about ever looking bad. But the general belief seems to be that if they just keep working on it, and just make the latest change to the UI or the algorithm, maybe, just maybe, they can "show" that they've somehow improved humanity.

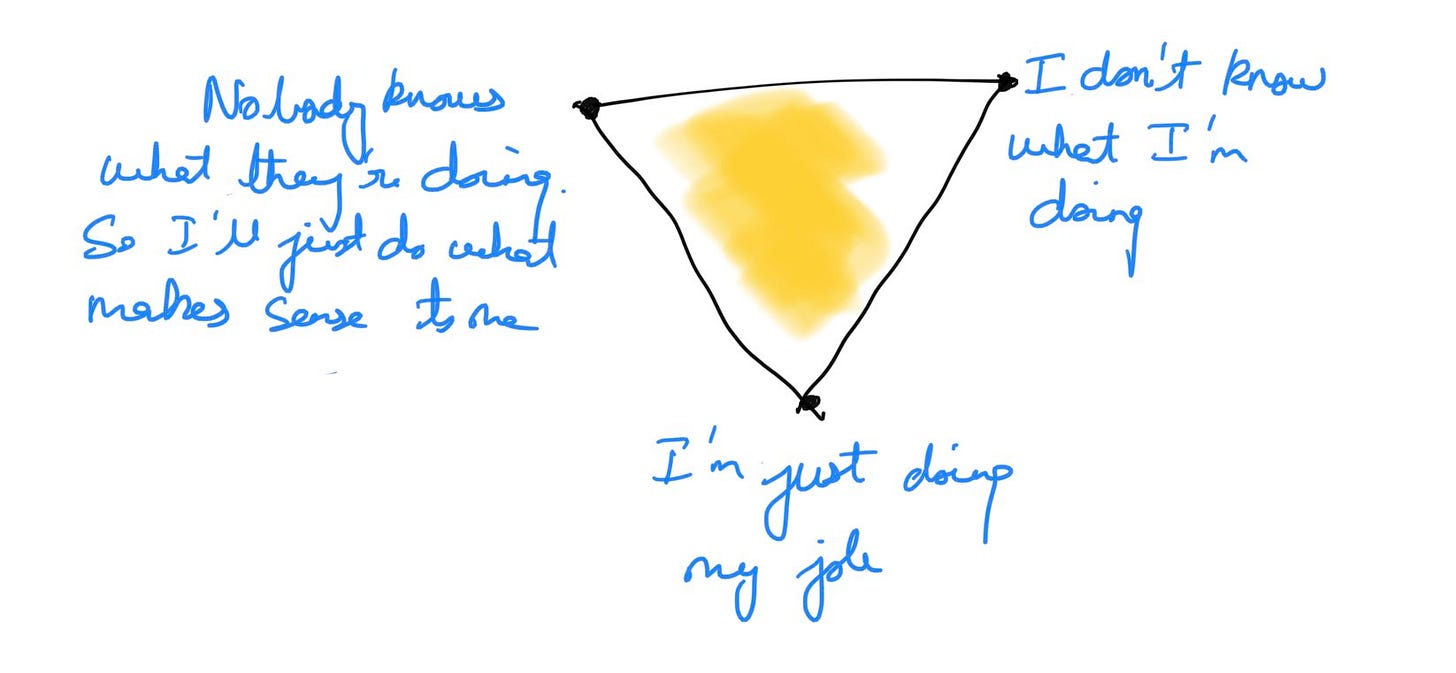

My own model for how people often make such decisions is:

Cause and effect

It does seem like Facebook's researchers have a better understanding of the many effects it has than researchers outside the company (this is not a comment on the quality of any researchers, it is largely a case of information access).

And while Nick Clegg (NYT reported on his leaked internal memo) and Andy Stone (see his quotes here) can always point to how certain issues are societal, or to the dollars/hours that Facebook spends, or its “strong track record” to do xyz - all of which sound nice. But do they, individually and collectively, move the needle in the direction we need them to (this is all severely complicated by the lack of consensus on what that direction is)?

Facebook can simultaneously be spending way more than competitors on enforcing its policies and research, have researchers who have a better understanding of its effects than anyone outside the company - and still, still, not have a deep enough understanding or focus their efforts at the wrong level.

I'm still thinking this through, here's my amateur illustration:

Assume Facebook effects on society flow radially outward from Facebook, its users, its decisions, etc. (note, this is only depicting Facebook, and is not meant to imply that Facebook IS THE ONLY entity that has outwards)

The Red blur close to the bottom is where out understanding needs to be.

The green blur represents internal researc’ers' understanding. Lower and broader than external researchers (blue blur), but still likely missing a lot.

The Red rectangle is whFacebook'sok's efforts are likely concentrating around i.e. not at the levels required to make a fundamental difference, and missing a lot of the issues.

Customary warning about not focusing too much on one company

Yes, I realise the contradiction of this coming in a section specifically focused on the same company (and the edition mainly stressing that section). But, for all the problems I have with Facebook (and there are many), I don't think wishing them away will solve many of these issues. The cat is out of the bag, and the horse has bolted. The milk has been spilt and is probably turning sour (I think you get the point).

Even if the seemingly re-energised FTC under Lina Khan, gets its way and breaks up the company at some point in the future - the effects (good or bad) of instantly connecting humanity are here to stay with us.

One last thing

I don't know too many people who would be excited by wonkish details such as this, but I thought this bit was fascinating (from the first article in the series).

A Facebook manager noted that an automated system, designed by the company to detect whether a post violates its rules, had scored Mr. Trump’s post 90 out of 100, indicating a high likelihood it violated the platform’s rules.

It is the first I've seen of this scoring system being documented (it is no surprise that they have one).

Rus(sia)hing to decisions

This section is adapted from Takshashila's Technopolitik #10

In the last few weeks, there have been two sets of significant developments involving Russia and the Internet:

After several weeks of sustained pressure from Russian authorities, in mid-September, Google and Apple removed a 'smart voting' app from Alexei Navalny's team just before the elections (Techmeme aggregation of related links)

As part of its efforts to deal with COVID-19-related misinformation, YouTube took action against two German-language channels operated by Russia Today. Russia threatened to retaliate by blocking YouTube and German media outlets.

These issues represent a microcosm of the myriad issues at the intersection of technology and geopolitics.

In this section, let's look at three of them:

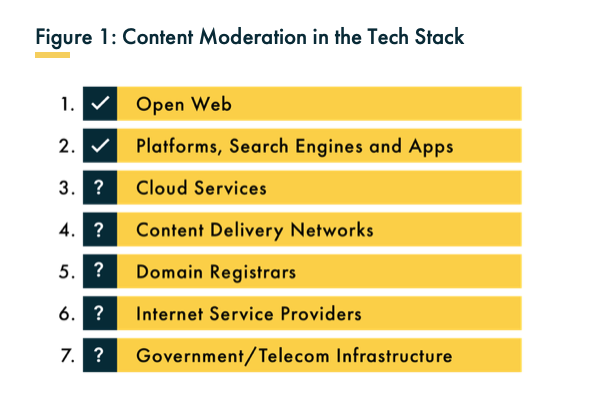

Content Moderation through the stack

Not only did Apple and Google remove the app from the Russian versions of their respective app stores, but they also took actions that had downstream effects. Apple, reportedly, asked Telegram to remove some channels that Navalny's team were using to share information or risk being removed from the App Store. Telegram complied.

These actions are neither new nor exceptional - but what is notable is that they have been praised (de-platforming Alex Jones' Infowars, Parler) or criticised (VPN apps in China, HKMAP.live during the 2019 HK protests) in the past, depending on the context. WSJ’s Facebook Files series also references Apple’s role in Facebook’s response to concerns about human trafficking. This is, of course, not specific to Apple, as a range of companies and services at different levels of the internet stack like AWS, Cloudflare, GoDaddy, etc., have had to make such decisions.

A particularly notable recent example was the case of OnlyFans, where the company announced (and later rolled back) policies that would have banned creators who posted adult content. The move was a result, not of any regulatory pressure or social backlash, but the apparent squeamishness of some firms in the financial services industry in the UK, which would have had an impact on creators around the world.

Complying with 'local regulation'

In the lead-up to Apple and Google removing the 'smart 'voting' app, they were threatened with fines, made to appear before committees where reports suggest that authorities named specific employees that would be liable for prosecution. A proposed Russian law requires that internet companies with over 500 thousand users in Russia set up a local presence. Similar regulation around the world has earned them the moniker of 'hostage-taking laws' as they open employees up to the risk of retaliation/harassment by state authorities.

The local regulation that led to Apple warning Telegram is believed to be one about 'election silence' - which prohibits campaigning during elections, which, being honest, is not unique to Russia.

Multinational companies operating across jurisdictions have had to 'comply with local regulation.' It was rarely an option until the information age, making it possible to scale across countries without establishing a physical presence. Even in the internet economy, companies that operate physical infrastructure deep into the tech stack often have limited choice. I have some personal experience with this, being part of a team that managed Content Delivery Network operations for China and Russia between 2015 and 2018.

Rapid and Global Scale Decision-making

When YouTube decided to enforce its COVID-related misinformation policies, did it anticipate that channels operated by Russia Today would be swept up by the enforcement action and did it expect threats/retaliation by Russian authorities? In 2021, there is no excuse not to, considering we have witnessed so many instances where technology companies found themselves in situations with geopolitical implications. Yet, we must stop and ask two questions. First, do they have the capacity to make these decisions on a global scale on a near-realtime basis? Second, do we want them to make such choices? Arguably, the order should be reversed, but we have to ask the capacity question in parallel since we're already in a situation where they make such decisions.

As US and allied forces were withdrawing from Afghanistan, sections of the press were heavily critical of social media platforms for continuing to platform Taliban-associated voices. Though, we also do need to take into account that nation-states with significant resources and capacity dedicated to international relations and geopolitics have, even now, yet to make a decision (this, of course, is likely strategic in many cases). But it does leave several open questions for private companies that often rely on nation-states for directionality. In this context, it is worth listening to this Lawfare podcast episode which draws parallels with the financial services industry and the mechanisms they can rely on to make decisions regarding dealing with banned groups.

I had written about this decision-making capacity and the velocity of society on SochMuch a few weeks ago.