Of 'Manufacturing Consensus', Worldwide Conduits and The FIR-ing line

The Information Ecologist 57

What is this? Surprise, surprise. This publication no longer goes by the name MisDisMal-Information. After 52 editions (and the 52nd edition, which was centred around the theme of expanding beyond the true/false frame), it felt like it was time the name reflected that vision, too.

The Information Ecologist (About page) will try to explore the dynamics of the Information Ecosystem (mainly) from the perspective of Technology Policy in India (but not always). It will look at topics and themes such as misinformation, disinformation, performative politics, professional incentives, speech and more.

Welcome to The Information Ecologist 57

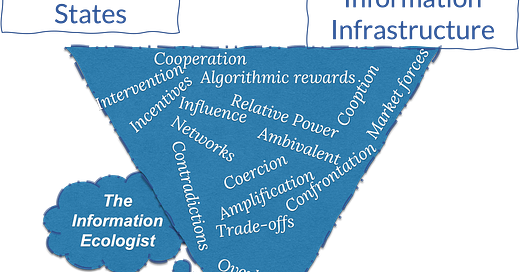

Yes, I’ve addressed this image in the new about page.

In this edition:

Manufacturing Consensus: Some points on the Tek Fog investigation - ok, 6.

Worldwide Conduits of Misinformation and Disinformation: Consortium of fact-checking organisations write an open letter to YouTube.

In the FIR-ing line: A tracker for Arrests / Cases / FIRs / Threat(s) / Detentions related to posts on Social Media

Hello to all the new subscribers who’ve come in over the last few weeks.

Fair warning: Things get pretty doom-y and gloom-y around here, but we’re optimists in the sense that we know things can always get worse 😃. And I tend to focus more on events in India (though not always).

Manufacturing Consensus

The title of this section is taken from something Samuel Woolley said on an episode of The New Abnormal.

Two of the most disturbing stories since the last edition of The Information Ecologist have been the ‘Bulli Bai’ app and The Wire’s Tek Fog investigation (if you’re new, consider this me making good on the warning from 2-3 lines ago). Regarding ‘Bulli Bai’, I co-authored an article with Tarunima Prabhakar, trying to place it within the broader context of the information ecosystem [The Indian Express].

Unless you’ve been living in a fog under a rock, there’s a good chance you’ve heard about TekFog. Now, there’s a lot going on here, but this section from the 2nd article in the series summarises it (also see parts 1, 3 and an explainer):

(1) hijacking Twitter and Facebook trends,

(2) phishing and capturing inactive WhatsApp accounts,

(3) creating and deploying a highly granular database of citizens for targeted harassment, and

(4) the possibility that its use is part of a political-corporate nexus linking the BJP to large tech players and platforms. Since the publication of our story, two of the companies which The Wire's source had named as having links to the use of Tek Fog – Persistent Systems and Sharechat – have issued statements denying any knowledge of the app.

The investigation seems to confirm what many of us already believe. And the authors do have some serious technical chops. I am not going to do a full-fledged dissection of the claims. Quite frankly, that’s beyond my capability. There is, however, plenty to be cautious about:

The investigation highlights the growing levels of sophistication at manipulating public discourse (or manufacturing consensus), and an ever-widening gap in terms of resources and possibly, capabilities between those trying to uncover these attempts/prevent.

I am genuinely curious if any other news publications reached out to the whistleblower based on the original tweet, which seemed to have publicly mentioned ‘Tek Fog’ for the first time in April 2020 (the authors link to it in the first post of the series). If they did, why did they choose not to pursue the story? If nobody else bothered to follow up - what does that tell us? I wonder if we’ll see an anonymous post about this (I’m not holding my breath).

It is vital that we do not walk away from this investigation thinking that all right-wing discourse is inauthentic, manipulated, manufactured < insert adjective here>. Even if most of it is, dismissing it risks discounting the participatory nature of our current information dysfunction (See 53: Participatory Dysfunction - which referred to a paper on the coordinated manipulation of Twitter trends), and the potential scale of radicalisation (See 55: The shrinking road from fear to hate).

Aside: See this extract from Jessica Stern’s article on the importance of not losing sight of the importance of emotional factors (emphasis added) [The Boston Globe]

… attributed their capacity to disengage from these violent movements more to emotional factors than to intellectual ones: support from their families, finding a new sense of purpose through work (including counseling others trying to disengage), developing trusting relationships with prison personnel or probation officers, and strengthening other types of prosocial relationships. They also referred to experiences that complicated their inhumane views of the “enemy” — such as a Muslim person’s explanation of what it felt like to be a member of a hated minority group as a child. Some have referred to their racist views as a kind of addiction.

How we carry these claims forward will be important. I expect (and this is just a gut feeling - so feel free to disregard) that the footprint of some of the capabilities that constitute TekFog (like the Whatsapp exploits, exploitation of cross-site scripting vulnerabilities to display manipulated text {text-fakes?}) is probably not that large. This sort of manipulation is far more decentralised than we often think (again, opinion) - like the paper in 53 demonstrated.

The criticism: Even as the stories were coming out - some questions/concerns were emerging (some samples — on the assumed use of Open AI (tweet), demonstration of the article modification (tweet): this was subsequently demonstrated to an extent- h/t @squeal & @64_BIT etc.) The most interesting criticism, so far, has turned out to be the one Samarth Bansal published in his newsletter. I did agree that some of the claims being made could have been demonstrated better or contextualised, but not necessarily with the framing and tone of it (it is his newsletter, though, and the framing/tone he chooses is entirely up to him). This has the potential to devolve into a semi-ugly spat (not to mention be co-opted by voices who want to downplay/discredit the entire investigation).

If you’ve been a long time subscriber, then you’ll recall that I used to dabble in some Twitter trend analysis here. But I quickly realised (in the context of my limited resources and skills), that it was a circular exercise - I could analyse twitter trends till the cows came home, post screenshots of hateful/bigoted content till my internet worked - but I would never get beyond that first level. There was always going to be a need for deeper investigative work to actually uncover some of the actors (in my head, this meant a combination of the OSINT analysis and some solid investigative journalism). The Tek Fog investigation should be considered the first step in that direction. Did it have some limitations? Sure. Is there room for improvement? Absolutely.

Worldwide Conduits of Disinformation and Misinformation

Last week, ~80 fact-checking organisations wrote an open letter to YouTube asking it to do more to deal with the amount of disinformation and misinformation on its platform [Poynter].

As an international network of fact-checking organizations, we monitor how lies spread online — and every day, we see that YouTube is one of the major conduits of online disinformation and misinformation worldwide. This is a significant concern among our global fact-checking community.

The letter referenced:

Conspiracy groups collaborating across borders - Germany, Spain, Latin America

Videos in Greek and Arabic that encouraged people to boycott vaccines

Amplifying hate speech against vulnerable groups - Brazil

Manipulation of election-related discourse - Philippines, Taiwan, US

Aside: Now, I should admit that when I read such content, I typically look for references to India. Why? Well, I do live there and write about its information ecosystem. So it did strike me as odd that there are no India-specific references despite there being somewhere in the range of 400-500M YouTube users in India [TechCrunch]. Also, 10 of the signatories were organisations from India. Let me clarify, I am not implying any ill-intent here. IFCN and all its signatories do essential work. But, as someone with an obvious bias, I am super curious about why this happened. There is certainly no shortage of the type of content referenced.

But setting aside that last… er… aside. This is pretty important. YouTube has gotten significantly less attention than Facebook, and even TikTok, in recent years. When there’s little reason it should not be subject to similar levels of scrutiny.

The recommendations themselves were sensible (obviously):

Transparency.

Move from leave-up/take-down binary and look at providing context, debunks, etc.

Act against accounts that repeatedly violate policies.

Build capability in languages beyond English.

This also reminded me of the concluding section in Chapter 4 of Noah Giansircusa’s How Algorithms Create and Prevent Fake News (the chapter itself is titled: Autoplay the Autocrats)

First, the cycle:

Over the past several years, we have witnessed a repetitive cycle in which a journalistic accusation or academic investigation faults YouTube’s recommendation algorithm for radicalizing viewers and pushing people to dangerous fringe movements like the alt-right, then a YouTube spokesperson responds that they disagree with the accusation/methodology but also that the company is working to reduce the spread of harmful material on its sitein essence admitting there is a problem without admitting that the company is at fault

Then, the unknowns:

YouTube’s deep learning algorithm provides highly personalized recommendations based on a detailed portrait of each user drawn from their viewing history, search history, and demographic information. This renders it extremely difficult for external researchers to obtain an accurate empirical assessment of how the recommendation algorithm performs in the real world. Nonetheless, the glimpses we have seen and discussed throughout this chapter—from YouTube insiders to external investigations to firsthand experiences of political participants and fake news peddlers—together with the undeniable context that large segments of society increasingly have lost faith in mainstream forms of media and now turn to platforms like YouTube for their news, are fairly compelling evidence that YouTube’s recommendation algorithm has had a pernicious influence on our society and politics throughout the past half decade.

Opacity:

What the current state of the matter is, and whether YouTube’s internal adjustments to the algorithm have been enough to keep pace, is unclear. What is clear is that by allowing this misinformation arms race to take place behind closed doors in the engineering backrooms of Google, we are placing a tremendous amount of trust in the company. As Paul Lewis wrote in his piece on YouTube for the Guardian, “By keeping the algorithm and its results under wraps, YouTube ensures that any patterns that indicate unintended biases or distortions associated with its algorithm are concealed from public view. By putting a wall around its data, YouTube […] protects itself from scrutiny.”

And… the adversarial space:

… even if YouTube voluntarily takes a more proactive stance in the fight against fake news, other video platforms will step in to fill the unregulated void left in its place. In fact, this is already happening: Rumble is a video site founded in 2013 that has recently emerged as a conservative and free speech–oriented alternative to YouTube

Mid-scroll call-to-action

(No personal data was used, everyone sees this)

In the FIR-ing Line

Since the last week of December, I’ve been quietly filing away any news reports that refer to police cases, arrests, detentions, FIRs (first information reports, for those unfamiliar) for social media posts, or based on social media posts (i.e. something was recorded and shared - which then ‘went viral’ {see Related below} and led to action).

For now, these are living on Notion Dashboard: Tracking Arrests / Cases / FIRs / Threat(s) / Detentions related to posts on Social Media. (I am open to alternatives, Notion still seems super clunky and has a bunch of usability issues, but it is low-friction when it comes to sending links to a database that I can categorise later - while pulling out my hair)

What Type of Cases will it include?

This is tricky, and can be subjective. But to act as a guideline - I will use Narrative Harms as we defined in a Takshashila Working Paper on Categorisation of Harms Attributed to DCNs (PDF Link - Narrative Harms are described from pages 12-15).

A by-product of this criteria is that individual cases of harassment, blackmail, cheating, etc., will probably not be included on the tracker. That should not be considered a comment on the consideration of their relative importance.

I also realise that there are some caveats here:

As Rukmini S says in Chapter 1 of Whole Numbers and Half-Truths

Not just statistics, most news reporting on crime too emerges from the FIR. Apart from the occasional daring investigation, the standard Indian crime reporter's practice is to faithfully reproduce the contents of an FIR as fact, in part to keep the police establishment happy. This reliance on FIRs is fraught with problems. Alongside acts of great bravery and hard work in trying circumstances, there is also extreme venality in Indian police forces. And, alongside genuine crime, there are also complex sociological forces that drive people into police stations, forces that have little to do with true crime. In short, FIRs alone say too little.

Since it relies mainly on news reports in English, it should neither be considered exhaustive nor representative. It can only be considered indicative. Just because one state appears more frequently does not automatically mean that it is more prone to do doing this - it could just be that it gets reported on more. Which, by itself, is a good thing - I’d rather have these stories written than not.

Ok, so what have I seen over the last 3 weeks?

Well, the cases around the Dharam Sansad’s in Haridwar, Raipur and ‘Bulli Bai’ have gotten plenty of attention. So let’s try and look at some of those that may have gone by relatively unnoticed (based on my judgement - I could, of course, be wrong about this)

Among the more interesting ones was this story from Telangana, where the police implied a need for a license to operate a YouTube news channel. I was not aware that this was a requirement. [Times of India]

Karimnagar police arrested two persons for operating YouTube news channels without seeking permission from the authorities concerned and allegedly posting offensive content against political leaders.

…

According to Karimnagar police commissioner V Satyanarayana, two persons from Huzurabad were operating the channels claiming themselves as journalists and posting content which was offensive to sections of population. “They have been arrested and two logos and two cellphones were seized from their possession. We will not allow if someone claims that he or she is a journalist without an accrediation card or an authorisation from a media organisation. We formed a special team to prevent spread of misinformation and posting of abusive content on social media,” the police commissioner said.”

While this story did not name the people nor the channels - another report indicates that on January 6th, “at least 40 journalists and content creators running Telugu YouTube news channels were reportedly arrested by the Telangana police”. This one references several sections of the law which were invoked [The News Minute]

“Unlike Musham Srinivas, Dasari Srinivas, who runs the YouTube channel Kaloji TV, was booked by the Balanagar police under the Cyberabad Commissionerate. He was arrested under sections – 505 (1) (b) (with intent to cause alarm or fear to public), 505 (2) (statements creating or promoting enmity, hatred or ill-will between classes), 504 (intentional insult to provoke breach of peace) and 153 A (promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc) – for making critical comments against KCR and his daughter K Kavitha.”

Another one from Telangana, this time implying that NRIs can have their passports revoked [The Hans India]

“Addressing a press conference, CP Stephen Ravindra said that strict actions will be taken against those who post controversial posts on Political, business, movie celebrities, innocent people, women and children.

…

He said that in addition to registering cases against those spreading fake news on social media, their passports will be seized and visas too will be cancelled as per the legal provisions.”

The tracker has more from Telangana. I’m not listing them here for now.

Sticking to the threats/warnings beat, in late December, Kerala police issued a warning to admins of Whatsapp groups. There is some context here, this happened in the aftermath of the murders of political functionaries.

It has been noticed that several messages, inciting communal hatred, are being circulated through social media after the murders of the BJP functionary Ranjith Sreenivas and SDPI’s K S Shan earlier this week, Kant said here in a statement.

“The admins of social media groups who permit discussions (inciting communal hatred) will be booked. The cyber wing of the state police has been asked to intensify its surveillance in all districts to check such propaganda,” he said.

Notably, around the same time, the Madras HC upheld a previous Bombay HC judgement which said that Whatsapp admins could not be held liable [LiveLaw - potential paywall]

Some whole numbers from Maharashtra [Free Press Journal]:

Police said that of the total 1,121 cases registered in connection to the fake news and hate speech in the state, over 1,055 were registered as cognizable offences while 66 were non-cognizable (NC). The cyber police made a total of 367 arrests, wherein 1,049 were identified, and notices were issued to them under the Criminal Procedure Code. The Maharashtra cyber police have made 367 arrests since the pandemic began for spreading fake news, rumours and hate speech in cyberspace. The state cyber police in the last week itself reported 466 cases of hate speech and communal crimes over social media.

If you go through the tracker, it is clear (and not surprising) that law enforcement authorities tend to act against opposition voices.

But, Prateek, why are you even doing this?

Great question! I had attempted to do this via a Twitter thread in 2020, and got to the mid-30s before it lost steam.

This is all building up towards answering the inevitable question of ‘should India have an anti-disinformation law?’. A question that was sparked off by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Information Technology’s recommendation to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to study such laws in other countries. See 54: Committee Reports, where I ended with:

All of this is to say is that we’re already (selectively) taking a lot of action based on what someone perceives to be false information, inappropriate comments through social media posts. We shouldn’t be too eager to go down the road of exploring blunt legislative instruments that are going shift the power dynamic further away from societies. At the very least, we should study existing laws and jurisprudence on the ‘prosecution of a lie’ first before we contemplate isomorphic mimicry. Ideally, this should be the Ministry of Law and Justice’s job.

So, coming back to this tracker. First, I am trying to understand the various ways in which the Indian state prosecutes false information, hate speech, etc., in the context of social media posts. Second, are there clear patterns of harms or benefits we can see once this builds into a sizeable resource?

I am happy to get more feedback on this. Feel free to reach out over email, or Twitter DM (if you don’t have my email address)

Related:

On the dynamics of ‘going viral’ - Jyoti Yadav has an important report on the role of video and virality in drawing attention to caste-based atrocities [ThePrint] (worth noting that it is not all good news though - Kranzberg’s First Law: Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral)

The smartphone video has become the latest weapon in the centuries-old caste war in Rajasthan. It is being used by Dalits to shine a light on atrocities committed on them by dominant castes who continue to oppress those lower down in the hierarchy. Tech-savvy Dalit youth are using their newfound, hand-held power to inform the law and order bureaucracy, even in the most remote villages. But virality is crucial. The police investigation only picked up momentum when Director General of Police (DGP) Mohan Lal Lather intervened after the video gained thousands of views.