What is this? The Information Ecologist (About page) will try to explore the dynamics of the Information Ecosystem (mainly) from the perspective of Technology Policy in India (but not always). It will look at topics and themes such as misinformation, disinformation, performative politics, professional incentives, speech and more.

Disclaimer: This is usually a space where I write about nascent/work-in-progress thoughts, or raise questions that I think we should (also) be looking to answer.

Disclaimer 2: This is not a systematic, professional activity. On the contrary, if you look at my process, you will see how utterly un-systematic it is. Thanks!

Welcome to/(back.. from the dead?) The Information Ecologist 64

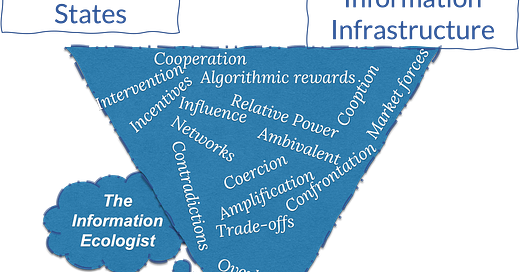

Yes, I’ve addressed this image on the new about page.

In this edition:

Where the hell was this damn thing, and what to expect now? See Postscript.

Refresher on tone/form: As always, I will continue to be polite and irreverent. And in general, my focus is on systemic issues, rather than individual actors - so you will rarely see me ‘call out’ someone as is customary on social media (I will name people when I am appreciating their work, of course). Oh, and prepare for an avalanche of outdated references.

Information Ecology: Symptoms, diseases and cures.

I know case numbers are going up again, but this is not about COVID-19.

Let’s get Poli-Tech-al: New Year Wishes that I hope MeitY will turn into resolutions.

Information Ecology: Symptoms, Diseases and bad medicines we don’t need.

Over the last few months, it has been possible to avoid the topic of ‘deepfakes’ / ‘synthetic content’. The increasing sophistication of generative AI tools does mean they are getting better, and when you combine with the poor levels of information literacy in India, and the current state of political discourse - which relies heavily on narrative-shaping rather then truth-telling, means this is going to significant challenge. And yet, I don’t think we can wish these challenges away by making the executive come up with a ‘legal framework’, ‘rules’, ‘regulations’. It shouldn’t be this un-obvious, frankly, we have only spent the better part of a decade wishing away and failing to address its more superset-y cousin - ‘Disinformation’.

It forms a part of a larger conversation about whether such issues are a disease, or manifestations of underlying problem (symptoms). Where one stands on this is significant, because it plays a role determining what one may consider the ‘cure’ to the problems.

Let’s consider three recent pieces that touch upon this consideration in different ways (None of these were written in the Indian context. Sometimes that’s not a bad thing as the distance allows for a dispassionate analysis):

Misinformation is the symptom, not the disease - Dan Williams

TikTok’s Influence on Young Voters Is No Simple Matter - Zeynep Tufekci (potential paywall)

Elon Musk, X and the Problem of Misinformation in an Era Without Trust - Jennifer Szalai (potential paywall) [I promise, I will not bring Musk into this]

As always, I will make my points using specific extracts, but I do recommend that you read all three fully. Also, cards on the table. I’m way closer to ‘think of them as symptoms’, rather than as a ‘disease’. Unlike Mr. Bonjovi (anyone remember?), I don’t need bad medicine (tbh, bad is too harsh, wrong is better, but I couldn’t find an appropriate outdated reference for it - other than a pill that instead of making you feel better, makes you feel ill).

But seriously, let’s start with the implications of the ‘disease’ model. As Williams writes:

The disease model of misinformation has practical consequences. If misinformation is a societal disease, it should be possible to cure societies of various problems by eradicating it. The result is intense efforts among policymakers and companies to censor misinformationand reduce its visibility, as well as numerous initiatives that aim to cure citizens of false beliefs and reduce their “susceptibility” to them.

The tendency with this model is also then to place the blame almost entirely (or certainly mostly) on social media platforms. As Tufekci writes (in the context of people (especially younger Americans) blaming TikTok for their views about Palestine, and the state of economy:

Young people are overwhelmingly unhappy about U.S. policy on the war in Gaza? Must be because they get their “perspective on the world on TikTok” — at least according to Senator John Fetterman, a Democrat who holds a strong pro-Israel stance. This attitude is shared across the aisle. “It would not be surprising that the Chinese-owned TikTok is pushing pro-Hamas content,” Senator Marsha Blackburn said. Another Republican senator, Josh Hawley, called TikTok a “purveyor of virulent antisemitic lies.”

Consumers are unhappy with the economy? Surely, that’s TikTok again, with some experts arguing that dismal consumer sentiment is a mere “vibecession” — feelings fueled by negativity on social media rather than by the actual effects of inflation, housing costs and more. Some blame online phenomena such as the viral TikTok “Silent Depression” videos that compare the economy today with that of the 1930s — falsely asserting things were easier then.

Aside: I love the term “vibecession” :P

Aside 2: None of this is to absolve social media platforms of their bad design choices, poor decision-making, and even active destruction of the public sphere. We’re at the stage where we do not fully understand the problem itself. Again, as Tufekci notes:

There’s no question that there’s antisemitic content and lies on TikTok and on other platforms. I’ve seen many outrageous clips about Hamas’s actions on Oct. 7 that falsely and callously deny the horrific murders and atrocities. And I do wish we knew more about exactly what people were seeing on TikTok: Without meaningful transparency, it’s hard to know the scale and scope of such content on the platform.

End of asides (for now)

The symptom model, on the other hand, urges us to look deeper (existing social tensions, inequality, experiences, and so on) - while the disease model focuses most of its attention on the existence of the false information itself. Williams writes:

the model of misinformation as a societal disease often gets things backwards. In many cases, false or misleading information is better viewed as a symptom of societal pathologies such as institutional distrust, political sectarianism, and anti-establishment worldviews. When that is true, censorship and other interventions designed to debunk or prebunk misinformation are unlikely to be very effective and might even exacerbate the problems they aim to address.

As a problem that needs solving, it is much easier to reconcile that the relative(s) you grew up has/have given in to hatred and bigotry because they read a lot of messages on WhatsApp, rather than that many of them bigoted to begin with (many of us do recognise this now, but it is a conclusion whose path is riddled with resistance). Yes, there is likely a feedback loop effect that prevalence plays, but there is also a reason it didn’t affect you, the person reading this (I don’t expect too many WhatsApp relatives to find their way here, tbh). Williams points to a market place of rationalisations that emerges as people seek information to conform with their worldview.

When it comes to domains such as politics and culture, human beings are not disinterested truth seekers. The competing sides in political debates and culture wars often behave more like warring religious sects than groups organised around coherent worldviews.

…

The result is a marketplace of rationalisations that rewards the production and dissemination of content that supports favoured narratives in society. We tend to view the super-spreaders of misinformation as master manipulators, orchestrating mass delusion from their keyboards and podcast appearances, but they are often better understood as entrepreneurs who use their rhetorical skills to affirm and justify in-demand beliefs in exchange for social and financial rewards.

Aside: Think of this also in the context how many ‘famous’ people in India are suddenly espousing majoritarian values.

There are other factors too. Let’s look at institutional distrust. Szalai references a Crisis of Authority and its role:

Which brings us back to trust. McIntyre’s appeal to the Army as a sterling source of trustworthy information will raise some readers’ eyebrows. A more clarifying take on trust is laid out by Chris Hayes in “Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy,” a book that was published in 2012 and turned out to be extraordinarily prescient. In it, Hayes describes how elite malfeasance — the forever wars after 9/11; the 2008 financial crisis — was deeply corrosive, undermining the public’s trust in institutions. This “crisis of authority” is deserved, he says, but it has also left us vulnerable. A big, complex democracy requires institutional trust in order to function. Without it, “we really do risk a kind of Hobbesian chaos, in which truth is overtaken by sheer will-to-power.”

Tufekci, references addressing the ‘broader sources of discontent’

Worrying about the influence of social media isn’t a mere moral panic or “kids these days” tsk-tsking. But until politicians and institutions dig into the influence of social media and try to figure out ways to regulate it and also try addressing broader sources of discontent, blaming TikTok amounts to just noise.

One major implication of the disease model, is that we try and cure the problem at the wrong layer. I will urge caution here, we shouldn’t be rushing to place (even more) power in the hands of actors who have consistently either failed us, or not demonstrated the capacity to deal with the complex nature of the problems i.e. the companies themselves, or the executive branch (the legislative and judiciary are not without their flaws either). Szalai, quotes Jeff Kosseff:

Where McIntyre calls for action, Kosseff, a professor of cybersecurity law at the United States Naval Academy, urges caution. He doesn’t deny that technology can amplify lies, and that lies — whether deliberately engineered or not — can be dangerous. But he points to “the unintended consequences of giving the government more censorial power.” Better, he says, to use measures already in place, including “counterspeech,” or countering a lie with a truth; and punishing people for the things they do (shooting up a pizzeria with an AR-15) instead of the things they say (falsely claiming that the pizzeria houses a pedophile ring).

…

Kosseff wants government agencies to embrace “candor” and “humility” when communicating with the public, and he promotes teaching media literacy to children — all of which sound reasonable.

The challenge, though, as Szalai points out (in the American context):

But at a moment when even elementary school reading lists generate rancorous dispute, any attempt to engineer our way out of our predicament throws us back on our profound disagreements over how to define the predicament in the first place.

Aside: In the Indian context, I am not holding my breath for candour and humility from government agencies.

This also means, that we do not solve this just by throwing facts at people (it is important to keep doing this, but it is a stem-the-flow intervention, rather than a fix-the-problem intervention). Here is what Williams, and Szalai wrote, respectively:

When this analysis of misinformation as a symptom rather than a disease is correct, many existing attempts to address the problems associated with misinformation are likely to be ineffective. Most obviously, if widespread false beliefs are symptomatic of deeper social pathologies, we should not expect to cure them just by censoring misinformation, and weaker interventions involving debunking or prebunking false ideas seem unlikely to change much real-world behaviour.

Aside: I don’t know about weaker, but certainly, targeted differently.

—

Recognizing how deep this crisis goes leaves us in a difficult place. Getting people to reject demonstrable lies isn’t simply a matter of bludgeoning them with facts. As the communications scholar Dannagal Goldthwaite Young writes in “Wrong: How Media, Politics and Identity Drive Our Appetite for Misinformation” (2023), the impulse to berate and mock people who believe conspiratorial falsehoods will typically backfire: “The roots of wrongness often reside in confusion, powerlessness and a need for social connection.” Building trust requires cultivating this social connection instead of torching it. But extending compassionate overtures to people who believe things that are odious and harmful is risky too.

The risk of backfiring (in this context, not to be confused with The Backfire Effect) is something Williams notes as well about interventions that rely on / can be portrayed as ‘censorship’:

…there is a real risk that censorship exacerbates the very problems it aims to address. For those who already distrust institutions, using those institutions to ban dissenting narratives seems likely to aggravate their distrust. Censorship is a flagrant display of power and disrespect towards those whose views are censored, and for the conspiratorially minded it is exactly what 'they' (e.g., elites, the establishment, and so on) would do to prevent people from finding the truth. Moreover, from its roots in the backlash to Brexit and the 2016 election of Trump, the current panic surrounding misinformation is undeniably partisan. Insofar as supporters of right-wing populist movements feel selectively targeted by censorship, as many do, this seems more likely to inflame polarisation than improve it.

But, I go back to Tufekci’s point about needing to understand the problem better. And I’ll ask you to think back to when was the last time you recall someone (a politician, a policy analyst) talking about the intractable challenge of disinformation, and needing to understand it better by supporting long-term research, capacity building in India, BEFORE jumping into ‘regulate’ (‘The government must..’ / ‘India must …’). Take your time, I don’t there are too many. Because it is an unsatisfying, slow-process and there is little credit to be taken, and a messy endeavour that needs long-term capacity and institutional building. Yet, “we must…”

On this, please read Simon Chauchard and Sumitra Badrinathan on research challenges (the piece, unfortunately requires institutional access. I don’t, I just asked for a copy. Reach out (to Simon) if you want one.

Let’s get Poli-Tech-al: All I want for the New Year is…

— Somewhere between a commentary and rant on technology policy developments in India. This section is a work of fiction (not news/current affairs) because it assumes a reality where the executive troubles itself with things like accountability, transparency, due-process, etc.

Ok, I want many things, but in the spirit of being realistic, I am going to limit it a handful of things that I want from MeitY (the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology).

Spoiler alert: these are all different ways of saying that the ministry should be held accountable. So, with the New Year, here’s hoping some of these will be adopted as New Year resolutions (I won’t hold my breath, and, neither should you):

1. A little more conversation, a little less distraction, please…

Why do I say this? 2 recent instances come to mind.

‘Deepfakes’ / Synthetic content:

This one has been quite a rollercoaster. One minister kept speaking about new ‘regulations’ or some such, and another about an ‘advisory’. One advisory was issued in November, and there was still mention of impending regulation (in 10 days, no less), and then an advisory, and we finally settled on… advisory (the contents are another matter, and a topic for another day) with a side of threats.

Data Protection Rules

One minister said something about a 45-day consultation period (which we thought was insufficient, given how many specifics of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 were left to rule-making). And then, another minister reportedly said that industry will get a week to respond. A week! (and no mention of a broader consultation, as of now).

Sitting on the outside, it is hard to say what led to this institutional doublespeak, and whether it is strategic or not. But what instances such as these (and many others over the years) do manage to do is to create confusion and ambiguity aplenty. One right hand not knowing what another right hand is doing reflects poorly on an institution, and is certainly not a plus if you’re Campbell + Goodheart Law-ing some ‘ease of doing business’ metric.

Recommended resolution: Pick up the phone / create a signal group / talk over ‘chai’ - do whatever it takes, but please, get on the same page.

2. Consult actually

(No, I did not watch Love Actually over Christmas, but did read <too-many-to-count> number of posts across Twitter, Threads, BlueSky, Mastodon, Instagram, newsletter references, that I may as well have [Yes, the placard business is strange as hell])

Let me apologise in advance for this coming across as a rant (more than usual), since it has been a cause of great anguish over the last few years. With each ‘consultation’ there will be tall claims of ‘extensive’ consultations [and there might be if you happen to be among a chosen few], numbers are cited about how many responses have been received, yada, yada, yada.

But, it seems like with most iterations, things that civil society point out, often get worse rather than better (Refer to government exemptions, and independence of a data protection body in successive drafts of the data protection bill).

Or, a new version will come out of nowhere, and past consultations on a very different draft will be cited (Refer to IT Rules, 2021 in February, 2021 which were vastly different from the Intermediary Guidelines that were put out for feedback in December 2018). (I wrote at length about the IT Rules process until the October 2022 amendments for an Asia-Pacific research clinic on Platform://Democracy. Look for the last essay)

Or, extremely consequential amendments with wide-ranging implications will be inserted along with a deadline extension for an ongoing set of proposed amendments, with a narrow stakeholder range (Refer to Gaming Intermediaries to the (infamous) fact-checking amendments pipeline).

Consultation responses themselves are not put out in the public domain (you know, I’m sure many of us would like to see what positions organisations/government departments are taking on matters that affect our rights), and are even denied under the RTI process.

Once in a while, there will be a ‘Dialogue’ prefixed with a ‘Digital India’ monicker where difficult, conceptual questions, or concerns about rights are met with a bristling derision (at least the ones I managed to get into - which is another story for another day over a tonic water), and those who point out problems are then asked to provide specific solutions, or at the receiving end of a lot of words that amount to ‘Trust me, bro!’.

And between all this, when changes are made (if at all), it is never really clear why certain changes are made from version to version like

Who got TDSAT into a data protection law??

What was the intention behind changing ‘shall cause the user not to’ to “shall make reasonable efforts to cause the user of its computer resource not to host, display, upload, modify, publish, transmit, store, update or share any information...”? What is reasonable and un-reasonable effort.

I could go on…

Or why some are consistently ignored, and even actively made worse. For all the talk of evidence-based policy, we seem to be subjected to evidence-free policy.

Receipts: This is not meant to be a particularly long point, so I will point you to some work where my colleagues have pointed out issues with the consultation processes. (I’m not even listing the ones where consultation papers vanished, or changed mid-consultation. Yes, that has happened.)

IT Rules Amendments, 2022 (link).

IT Rules Amendments, 2023 (link).

draft Data Protection Bill, 2022 (link).

Data Protection Bill, 2023 (link).

Recommended resolution: Stop the ‘consultation theatre’, and actually engage in good-faith.

3. Coming Soon… very soon, ok, maybe half-past soon-ish, may be not, perhaps, this week, next week, soon… you’ll see.

(Cue Sunny Deol in court screaming about dates)

Look, no one denies that the problems are complex. A little honesty (intellectual and otherwise) will go a long way. It is one thing to say we want to create a Open, Safe, Trusted, Accountable internet, and quite another to actually get there. I mean, just look at what political parties themselves are doing on the internet.

See, for example, the artist known as ‘Digital India Bill / Act’. Back in February, 2023, yes almost a year ago, my colleagues documented some press coverage about its impending nature, inlcuding some of earliest references to it by name (that we could find) from April 2022 (see screenshot).

Here, we are, 11 months later, and it is still… pending. Now, it may actually be put out for consultation very soon (doesn’t hold breath, again), but if I missed this many self-stated timelines on a crucial deliverable - many questions would be asked.

<Digression> (you have been warned):

Again, let me add, that this is by no means an easy undertaking. Countries with way more sophisticated (I am being very kind to us, did you see what happened in the 2023 Winter Session?) law-making processes are struggling / have struggled with this, gotten this wrong to degree (Hello, UK Online Safety Act), etc. But it baffles me endlessly that we are yet to see a clear articulation of any of the following in the Indian context (note, how otherwise, so many lawmakers and policy analysts are quick to point out that what applies in the West, need not apply to India)

A clear articulation of harms that people in India face on the internet. (Not in the Indian context, but I did attempt this)

What are the current laws that apply to these harms, and a clear assessment of where they fall short (this was not even a passing reference in the tearing hurry to shock-doctrine the criminal justice system).

What are the benefits? Look, we run around saying things like we must maximise the benefits and minimise the harms [guilty!], but really, what are these benefits? (I did try, you may or may not agree)

There are going to be many, many, strong views and voices on this. Plenty of disagreements, pushback, etc. How are we going to ensure everyone gets a genuine say (not just a mygov.in page, where there is no transparency about how/what feedback has been taken into account)?

How are we going to negotiate these trade offs? Because negotiating tradeoffs, is what the policy making process is about.

This is undoubtedly going to be (and needs to be in the true democratic spirit) a messy, difficult conversation with a lot of negotiations. But, I guess if one treats Opposition MPs as an inconvenience to be disposed off, then serious public discourse and conversation is a pipe-dream).

</Digression>

Another demonstration of this inability to make up a timeline (What? Isn’t that what’s happening?) and then meet it, is whatever is happening (or not happening) with the Data Protection Rules. In October, we were going to get 45-day consultation period for all the rules together. Then, in December, we were suddenly getting 7-days for a specific subset of the total set of rules, with the rules due to be ‘notified’ in the first week of January (i.e. the consultation [even if just theatre], should have at least started by now?]

The minister said that rules related to notice and consent mechanisms, processing children’s data, personal data breaches, data retention, and exercising user rights, are among the issues on which rules will be notified in the first week of January.

Look, I get things can change, and that’s fine. When they do - there should be a clear communication and acknowledgement. And when this happens repeatedly, there needs to be admission of fault/inability and introspection.

Recommended resolution: See what Jeff Kosseff said in the previous section about communicating with candour, and humility. Also, learn how to forecast a realistic timeline.

Postscript - Where was this?

Hello,

You may be wondering why I haven't published in so long, or even who I am (since you probably subscribed during a hoarding spree, and now have too many to read anyway). I don't think I have an excuse that can explain over 18 months of inactivity, so I won't. But a lot did happen, good and bad. I got a new job, and a massive increase in responsibilities, I moved cities, twice (not as exciting as it sounds, it was a to and fro movement, really), made some new friends, built new relationships, said goodbye to some significant ones, etc. etc. But anyway, here I am, hoping to pick up writing about the Information Ecosystem in the (mostly) Indian context regularly. I should end with a disclaimer though. The Information Ecologist (or MisDisMal-Information as some of you may know it as), has always been an exploratory space. Where I play around with ideas, opinions, and largely, attempt to make sense of the world through writing about things. Anything I say here, should not be considered to be the institutional position of the Internet Freedom Foundation, where I now am.

Oh, a short note on format - because I'm pretty much starting over, the format is going to be a little fluid for now. I'm re-learning this, I guess, and you get to come along for the ride (unless, you choose to unsubscribe, of course).

There is a question of why now, though? Again, I don’t know that I have a precise answer. But, it has been a while (over 18 months, in fact), since I have written, just for the process of writing, and learning, and having some fun with it.