Of Elections, Partisan Groups, Content and Ads

The Information Ecologist 62

What is this? The Information Ecologist (About page) will try to explore the dynamics of the Information Ecosystem (mainly) from the perspective of Technology Policy in India (but not always). It will look at topics and themes such as misinformation, disinformation, performative politics, professional incentives, speech and more.

Disclaimer: This is usually a space where I write about nascent/work-in-progress thoughts, or raise questions that I think we should (also) be looking to answer.

Welcome to The Information Ecologist 62

Yes, I’ve addressed this image in the new about page.

In this edition:

Elections and Partisan Groups, Content: What kind of content is prevalent in party-managed, local-level WhatsApp groups.

Elections and Political Ads: Some comments/thoughts about the Facebook Political Ads series, which recently appeared on Al Jazeera.

This edition has quite a few embedded images, so if you’ve blocked images by default (you should), I recommend clicking through to the substack page, or specifically downloading images for this message if your email client allows it.

Elections and Partisan Groups, Content

By the time you read this, it would have been approximately 2 weeks since the results of the most recent set of assembly elections in India came out. Results that were hugely positive for the BJP. 2 reasons (among many others) often brought up to explain its electoral successes are (there are many others. But, I don’t fancy myself a political analyst and let’s be honest, you don’t come here for my political analysis anyway):

Financial resources at its disposal.

Its domination of social media, in general, and WhatsApp in particular (you can certainly make the argument that 2 follows from 1).

Let’s look at some recent (and not so recent) literature that explores 2.

First, an October 2020 paper by Gursky, J., Glover, K., Joseff, K., Riedl, M.J., Pinzon, J., Geller, R., & Woolley, S. C. which looked into Propaganda on Encrypted Messaging Applications (EMAs) in the US, Mexico and India [Center for Media Engagement]. Note: As far as I can tell, this paper didn’t involve large scale content analysis.

We conducted 32 interviews with producers of EMA-based propaganda and experts on this phenomenon and combined insights from these interviews with an analysis of country-specific and global news coverage of EMAs, dis- and mis- information, and propaganda in order to identify trends in political usage of these apps.

It notes 4 trends relevant to Whatsapp + disinformation (all of these will seem familiar)

Rumours that have led to lynching/deaths.

Volunteer-powered ‘IT Cells’.

Politically partisan content (it noted that ‘most false political content’ favoured ‘Prime Minister Modi and the BJP.’)

Content sowing division between Hindus and Muslims.

Specifically, on the BJP’s usage, it makes the following points.

Crowdsourcing local news stories that are then framed and amplified at a national level. Viewing it as a ‘democratic equaliser’. This point was made within a broader point about volunteers and IT cell workers creating thousands of Whatsapp groups, and members of the BJP.

work(ing) with “volunteers, graphic designers, a few who are good on videos” to create engaging content.

Whatsapp’s restrictions aimed at creating friction may have entrenched their dominant position (this should not be treated as an argument to say that Whatsapp should not have taken any such steps, only makes a point about *one of the many* outcomes):

When questioned about the consequences of WhatsApp’s new forwarding limitations and other regulations, they asserted that, due to the networks being maintained through humans and not automated processes like bots, they are not a worry:

It works (sic) in our advantage… if you have people at every level, if you have people-to-people contact, then it doesn’t stop… It;s like you just pass the baton from one to each other… Whatsapp does not say you cannot forward the message to anyone. Whatsapp, in a way, they are just stopping tools.”

Shivam Shankar Singh made a similar point in a podcast episode with Amit Varma back in October 2021 (sorry, I know it is a long episode, and I don’t remember the approximate timestamp). As far as I recall, his contention went beyond Whatsapp to include things like KYC for mobile connections, etc. [The Seen And The Unseen].

The sentence preceding the quote above points to the people-intensive nature of the operation:

The interviewee stressed the scope and multi-level (from local to nationwide) nature of the WhatsApp groups he maintains and the significant time investment required to maintain them.

This is something for those of us who believe that Whatsapp does not have an algorithm to think about. Yes, Facebook itself does not push a newsfeed-esque centralised algorithmic selection interface onto its users. But there is a decentralised, people+money-powered distribution system in the mix (prevalence is another question, though) which mimics one, and cannot be controlled without unintended consequences. Aside: In general, these dynamics apply to Telegram, which is also a ‘non-insignicant’ venue (if I can call it that).

Did someone say prevalence? What percentage of content in Whatsapp groups maintained/managed by political parties is false information? And, at what levels are they a concern? An insightful paper by Simon Chauchard and Kiran Garimella addresses the first question to some extent [Journal of Quantitative Description]. Based on interviews of around ~2900 (300 polling booth areas from 10 districts in UP) social media managers booth level Whatsapp Groups ( over 2/3 were BJP) + visual content analysis of 533 groups over 9 months in 2019. They found (emphasis added):

Results suggest that misinformation and hateful content, while they account for an important part of some sub-types of content (for instance, content about minorities on the ruling party’s threads), remain overall rare: they account for only a few percents of the total content posted on these partisan threads, including on BJP threads. More surprisingly maybe, most of the content cannot easily be classified as “partisan content”. Salutations and wishes, often formulated in religious terms and/or relying on religious iconography, constitute much of the content. A large share of the content is also neither partisan nor religious, and more easily classifiable as phatic (Berriche and Altay, 2020) or entertainment-related. Only a small share (19%) of NaMo app content eventually ends up on the WhatsApp threads. More importantly, it is far from being the content most frequently shared by users on the threads, which suggests – coherent with our codings – that this content would most likely be drawn in a sea of other, unrelated content.

Aside 1: The part about salutations and religious iconography reminded me of a paper by Sumitra Badrinathan and Simon Chauchard about using religious messaging to counter COVID-19 related misinformation [Preprint on Github].

Since content analysis on groups was based on the group admins providing access, you could argue that selection bias could have played a role, and they only got access to ‘PG’ groups. And while they do not rule this out, the authors do provide reasons for believing that this may not be the case on Page 8. They are paraphrased here.

4 reasons why analysis is informative despite the potential for selection bias.

Groups not un-monitored/secretive, members added on weak ties.

Admins would not have known what kind of content the researchers would have considered problematic, and unlikely that they themselves considered it problematic.

Over time, Admins could have forgotten that they had added the researchers.

Members did not know about the researchers at all.

Also worth noting that the experiment was designed to overestimate the percentages of content that could be classified as hateful or false.

In both cases, (coders) were asked to err on the side of caution before answering “No”. If they were unable to properly justify such a ”No” coding, they were asked to choose the ”possibly” response category. This strategy implies that our estimates - presented below - of the amount of hateful content and misinformation present on the threads are by design likely overestimates.

Ok, so what percentage of content could be considered hateful or false?

This evidence already suggests that any such consequence likely does not owe to a potential “carpet-bombing strategy” which would see users being mostly plied with hateful content, as the vast majority of content we code does not fit this category.

Aside 2: The ad.watch/Reporters Collective series referenced later does indicate that lower prevalence may be strategic in some instances. Though, one cannot say conclusively whether or not that is the case with these groups.

Is this high? Is this low? What are the thresholds at which the prevalence of hateful and/or false messages have irreversible effects on society? We don’t know.

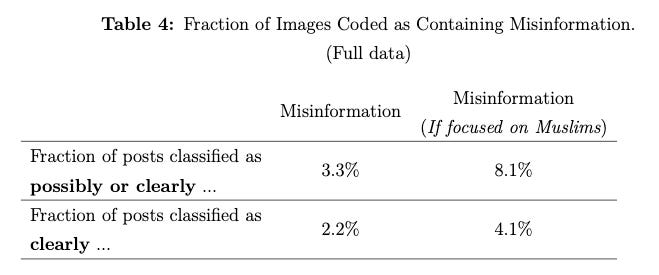

The analysis further looks at the prevalence of hateful and/or false messages about Muslims, and specifically within BJP groups (further differentiated as posts from admins and members). Unsurprisingly, there is a marked increase in prevalence (screenshots of relevant tables included). I should point out that the overall prevalence of content about Muslims itself was somewhere in the 2% range.

While <2% of images were tagged as hateful, around 20% of images categorised as being about Muslims were tagged as hateful. And when you look at BJP groups, this number rises closer to 40%. Also, 4% of the images posted by admins were tagged as hateful.

Similarly, for false content: While 2-3% of all images were tagged as false, 4-8% of images about Muslims were tagged as false (depending on whether you include possibly false content). In BJP groups, the percentage of images about Muslims tagged as false information were in the 5-11% range. Note how the deltas with hateful content are higher than those for false content. Also, in BJP groups, 5-6% of the content posted by admins were tagged as false.

Aside 3: Something that got my attention but I wasn’t sure how to interpret is the reduction in percentages of images tagged as hateful/false in the BJP Groups compared with the overall sample. Was there marginally lower prevalence in these groups, or was this an artefact of the content type (i.e. images), or of the relative number of groups (recall that 2/3 of the initial sample were BJP groups), or just down to more content, in general? This is something I hope to clarify with the authors someday.

What about Partisan content?

Well, it constituted less than 50% of the images.

Here too, the prevalence of partisan content seems to be higher on non-BJP groups. And, as the image below appears to indicate, members in non-BJP groups seem to share significantly more partisan information than members in BJP groups (black bar v/s green bar).

The section on non-partisan content indicates that most of these cannot be categorised (categorised as ‘Other’).

Besides, a follow-up analysis carried in the Fall of 2021 of the content classified under our residual category (”other” in Figure 4) confirms that the non-partisan content largely consists of content that does not easily lend itself to political or partisan propaganda.

Elections and Partisan Political Ads

Between 14th and 17th March, the reporters collective, ad.watch, and Al Jazeera published a 4-part series on political ads on Facebook in India [The Reporters Collective].

Let me first say that I think this was an important investigative series. I’d go even further and say that instead of being a one-off investigation, periodic studies of political ads in the Indian context are required. And I hope this ends kicking off more such collaborations between researchers and investigative journalists. I will make a few meta points and point out some quibbles I had, but before that, I recommend that you read the whole series.

How a Reliance-funded firm boosts BJP’s campaigns on Facebook (Part 1)

Inside Facebook and BJP’s world of ghost advertisers (Part 2)

Facebook charged BJP less for India election ads than others (Part 3)

What helps India’s BJP get lower Facebook rates? Divisive content (Part 4)

As is evident from the headlines, Parts 1 and 2 are about a network of ‘surrogate/ghost advertisers’ on Facebook. Parts 3 and 4 are about the system for targeting ads which results in the BJP getting charged lower rates for the same amount of views. For the lack of a better term, I will refer to these the ‘ad system’ stories.

The surrogate/ghost advertiser parts include some scary numbers. From Part 1:

From February 2019 through November 2020, NEWJ placed 718 political advertisements over a period of 22 months and 10 elections, that collectively were viewed more than 290 million times by Facebook users, according to the Ad Archive data. The company spent 5.2 million rupees ($67,899) on these advertisements.

Aside 4: As per Part 1, NEWJ posted primarily pro-BJP content. It also refers to a potential strategic interspersing of partisan and non-political content (see Aside 3 earlier)

These advertisements were carefully spread out among a relentless stream of non-political, informational videos about India’s history and culture or viral videos – such as a disabled woman writing a university exam with her foot – that NEWJ posts to capture eyeballs for its social media channels.

Part 2 suggests that an entire network of surrogate advertisers doubled ‘the views’ for the pro-BJP ads (as far as I can tell, there was no reference to reach, i.e. how many more people saw these ads)

These ghost and surrogate advertisers got almost as many views as the advertisements officially placed by India’s governing party, doubling its visibility without the party having to take responsibility for the content or the expenditure related to their advertisements.

…

TRC found the BJP and its candidates officially placed 26,291 advertisements by spending at least 104 million rupees ($1.36m), for which they got more than 1.36 billion views on Facebook. That apart, at least 23 ghost and surrogate advertisers also placed 34,884 advertisements for which they paid Facebook more than 58.3 million rupees ($761,246), mostly to promote the BJP or denigrate its opposition, without disclosing their real identities or their affiliation with the party. These advertisements got more than a whopping 1.31 billion views.

As far as I can tell, the surrogate/ghost advertiser analysis did not include regional parties, but there were some pro-Congress surrogate advertisers (tiny by comparison).

Part 1 points to a clear enforcement gap on Facebook’s part:

Facebook rolled out a policy in 2018 to verify the identity and address of people who place political advertisements. It now asks all such advertisers to declare who is paying for the advertisements and displays the details of the funding entity in the Ad Library. Facebook, however, does not verify whether the identity disclosures by the advertiser is truthful. Nor does it check if it might be funding those advertisements on behalf of political parties or their candidates.

But there’s a seemingly impossible problem here. A likely (and even intuitive) outcome is to want to fill that enforcement gap through greater state control/government oversight/institutional (e.g. the Election Commission) oversight. But let’s step back and look at who we are handing the reins over to. The same government we’re accusing Facebook of kowtowing to/favouring. The same government that wants to introduce ‘stricter laws’ to regulate social media, and indicated to the opposition that it should accuse it of ‘attacking freedom of speech’ [Hindustan Times]. The same set of institutions that we’re constantly claiming are crumbling and are no longer independent of the executive.

Aside 5: So, I was concerned when it was reported that Sonia Gandhi called for ‘curbs on social media’ [PTI - Economic Times]. However, and perhaps I am interpreting her statements too generously, if you read the text of her Zero hour intervention, it doesn’t seem like it explicitly called for curbs/regulation. Instead, it was phrased as the need to end interference and influence after making references to the lack of a level playing field. Of course, how that’s interpreted is a different matter.🤷♂️ [Uncorrected Lok Sabha Debate for 16/03/2022]

I urge the government to put an end to the systematic interference and influence of Facebook and other social media giants in the electoral politics of the world's largest democracy. This is beyond partisan politics.

Now, let’s move on to Parts 3 and 4 that covered the ‘ad system’. And this is where things get a little fuzzy for me.

The central assertions are that (heavily heavily paraphrased. Again, read the actual articles):

On average, the INC had to pay ~30% more for the same number of views than the BJP. In fact, in 9 of 10 elections that were reviewed, the BJP got better prices.

The divisive/popular content that BJP and its surrogates post combined with Facebook’s incentives to maximise engagement results in these lower prices.

Now, thanks to Facebook’s opacity - there are so many unknowns here that we remain in hypothesis territory after this. As I was reading the early bits of part 3, a few possible reasons for differential pricing occurred to me.

Bulk pricing/volume discounts.

BJP + surrogates just know how to target their ads more cost-effectively.

BJP + surrogates are less concerned with the quality of targeting.

… (remember, we’re dealing with a complex and opaque system, so there is unlikely to be any single satisfactory explanation).

1 can be reasonably ruled out. An analysis by The Markup that Part 4 refers to explicitly states that [The Markup] (this quote is from an accompanying ‘show your work’ post linked to):

(Facebook doesn’t offer bulk discounts, so the number of ads doesn’t directly affect their pricing.)

Aside 6: Incidentally, this is also the scene of one of my quibbles. Despite this, Part 4 says:

Facebook is not unique in offering discounts systematically to its biggest clients. Many brick-and-mortar businesses have always done this. So why have Facebook’s ad pricing policy raised questions across several democracies?

Maybe ‘systematically’ is doing a lot of work here. Still, it does seem to indicate that volume discounts are a possibility (or perhaps I am reading too much into it) which are ruled out by an investigation referenced later.

But let’s set that aside… er… aside for now. Part 4 does explain that while auctions ‘typically’ go to the highest bidder, Facebook’s policies do allow for situations in which a lower bid can win the auction to place an ad in a user’s timeline if it determines that engagement is more likely. So, while this does not rule out potential reasons 2 and 3, this does create some ground for the hypothesis that divisive/popular content + incentives for higher engagement led to cheaper ad rates for BJP + surrogates. This is because the divisive content may have been considered more likely to elicit engagement and thus may have been inserted into timelines more often (note the distinction between more often and of more people because we simply do not have data about the latter) even at lower bids.

In my interpretation, Al Jazeera classifying this as an Economy / Business and Economy story suggests that it thinks Facebook is the primary antagonist here, followed by the BJP (your interpretation might be different, and that’s fine).

I have ZERO sympathy for Facebook, but if my interpretation is correct, I think that’s an inaccurate frame. Even if you believe that all ad views lead to persuasion (which is a stretch), and ad targeting is this incredibly precise enterprise (also contested, for both - see Tim Hwang’s book The Subprime Attention Crisis), the fact that divisive content (as per the hypothesis) is overwhelmingly popular is a more fundamental concern in my view (unless you believe that a 100% of this popularity is inauthentic/astroturfed, which is highly highly very highly unlikely). Of course, Facebook’s opacity / poor enforcement are huge problems. I would just want to remind anyone tempted to think/want to believe that this is the ‘primary reason’ for the electoral misfortunes of their ‘party of choice’ - you know better. All other things being equal, if, in the next set of elections, Facebook ensures that all political ads cost the same - I still don’t foresee a significant shift in electoral outcomes.

Just as it is important not to do a ‘Nick Clegg’ (attempt to absolve social media companies by blaming everything on existing societal issues), it is also important not to do a ‘reverse Nick Clegg’ (apportion all/too much blame on social media for societal problems). Facebook’s responses weren’t particularly encouraging, from Part 4.

In response to a list of detailed questions over email, Meta said: “We apply our policies uniformly without regard to anyone’s political positions or party affiliations. The decisions around integrity work or content escalations cannot and are not made unilaterally by just one person; rather, they are inclusive of different views from around the company, a process that is critical to making sure we consider, understand and account for both local and global contexts.”

This is good PR speak and all, but it is incumbent on Facebook to realise it neither operates in a neutral world nor is it neutral itself.

Related: See this paper by Bridget Barret, which asserts that (in the US context) Facebook and Google are consequential actors in party networks [Political Communication].

Anyway, as I said earlier, I think this series is very important, and I hope this spurs on similar/related/adjacent research.

Questions that we should be looking to answer in future analyses in the Indian context (this is a non-exhaustive wishlist)

More research about the adtech space in general. I think I’ve said this repeatedly, but there is a dearth of such research and understanding in the Indian context.

The link between views and persuasion. This needs to happen in the context of both ads and content. I remain sceptical that views = persuasion. Also, in the absence of any information about ‘reach’, we cannot say whether or not the difference in the number of views was due to repetition, being shown to more people, or some combination of these. This is another scene of one of my quibbles - as far as I can tell, the coverage of this series by other news media outlets did not raise these points, even as a footnote.

More research that aims to explore Facebook’s ad pricing mechanism.

What would an analysis of ghost/surrogate advertiser networks for regional parties look like? It will be little/no consolation to learn that other parties do it too but are just ‘less efficient’ than the BJP.

Clearer attribution of more surrogate advertisers. I think this investigation made a start, and future iterations of such analyses need to make more connections that are also harder to deny - find that proverbial ‘smoking gun’.

P.S. I do not know why I have referred to my various quibbles as being in scenes. 🤷♂️

Post-Scroll Ad

I think it is fitting that I include a non-targeted* ad at the end of this edition. No, but seriously, if you’re reading this, then it is likely you have a keen interest in, or a super curious about technology policy in India.

You can find out more about the programme here.

*Everyone reading this edition or viewing it on the web, sees the same ad.