Of Anti-vaxxing eloquent, doom profiting, political superspreaders and the ‘Right’ kind of social media

MisDisMal-Information 26

What is this? This newsletter aims to track information disorder largely from an Indian perspective. It will also look at some global campaigns and research.

What this is not? A fact-check newsletter. There are organisations like Altnews, Boomlive, etc. who already do some great work. It may feature some of their fact-checks periodically.

Welcome to Edition 26 of MisDisMal-Information

Anti-vaxxing Eloquence

Let me start with asking you a question. Do you believe there is an ‘antivaxxers movement’ in India? A year ago, I would have laughed at the very notion. Today, I am not so sure. Maybe it is just a function of the information sources I choose to bury myself in. After all, I do go out of my way to look for such content more often that others would. But, I have been running into, let’s call them ’sceptics’, for now, outside of these sources too. But, as this BloombergQuint article (based on a survey by Ipsos) shows, support for getting a COVID-19 vaccine when available is high in India.

*So this is good news, no, Prateek? Why are you panicking?*

Because, panic I do and panic I must. Ok, but seriously. Yes, this is positive for sure.

The detailed report had some other interesting observations too.

A footnote on page 3: Online samples in Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and South Africa tend to be more urban, educated, and/or affluent than the general population. And on page 8: “The survey results for these countries should be viewed as reflecting the views of the more “connected” segment of their population.”

Among the people who said they would not get a vaccine, the number who said they don’t believe in vaccines in general was at 19%, lower only than South Africa. (Page 6)

52% of the respondents from India ‘strongly’ or ‘somewhat’ agreed with the statement ‘The chance of getting of COVID-19 is so low that a vaccine is not necessary.’ U.S. was the next highest at 31%. (Page 7)

Also, keep in mind though, that these opinions reflect a point in time. And remember that we live in an information ecosystem where narratives and conspiracy theories flow across borders (QAnon-variants are even finding a footing in Japan and Brazil).

In the book, Post-Truth, Lee McIntyre dedicates a chapter to Science Denialism as the pre-cursor for ‘post-truth’

The goal here is a cynical attempt to undercut the idea that science is fair and raise doubts that any empirical inquiry can really be value neutral.

If the “proof” game cannot be won, so we are going to play the “evidence” game instead, then where is your evidence, one might wish to ask the science denier.

Essentially, as he states ‘doubt’ is the product. Later, he argues in the context of the anti-vaccine movement that it was made worse by the willingness of established media to indulge in both-sidesism.

on the subject of the alleged link between vaccines and autism, based on the bogus research of Dr. Andrew Wakefield in 1998. Here the drama was even higher. Sick kids and their grieving parents! Hollywood celebrities taking sides! Maybe a conspiracy and a governmental cover-up! And again, the media failed utterly to report the most likely conclusion based on the evidence: Wakefield’s research was almost certainly bogus. He had a massive undisclosed conflict of interest, his research was unreproducible, and his medical license had been revoked. This was all known in 2004, at the height of the vaccine-autism story.

The rise of social media has of course facilitated this informational free-for-all. With fact and opinion now presented side by side on the Internet, who knows what to believe anymore?

Recently, the New York Times covered an astroturfing campaign:

In early 2017, the Texans for Natural Gas website went live to urge voters to “thank a roughneck” and support fracking. Around the same time, the Arctic Energy Center ramped up its advocacy for drilling in Alaskan waters and in a vast Arctic wildlife refuge. The next year, the Main Street Investors Coalition warned that climate activism doesn’t help mom-and-pop investors in the stock market.

All three appeared to be separate efforts to amplify local voices or speak up for regular people.

On closer look, however, the groups had something in common: They were part of a network of corporate influence campaigns designed, staffed and at times run by FTI Consulting, which had been hired by some of the largest oil and gas companies in the world to help them promote fossil fuels.

Anumeha Chaturvedi wrote in the Economic Times quoting Jency Jacob and FactCrescendo - who expect confusion and information disorder around the vaccine (screenshot of the quotes).

The AFP quotes the head of WHO’s immunisation department:

Rachel O'Brien, head of the WHO's immunisation department, said the agency was worried false information propagated by the so-called "anti-vaxxer" movement could dissuade people from immunising themselves against coronavirus.

"We are very concerned about that and concerned that people get their info from credible sources, that they are aware that there is a lot information out there that is wrong, either intentionally wrong or unintentionally wrong," she told AFP.

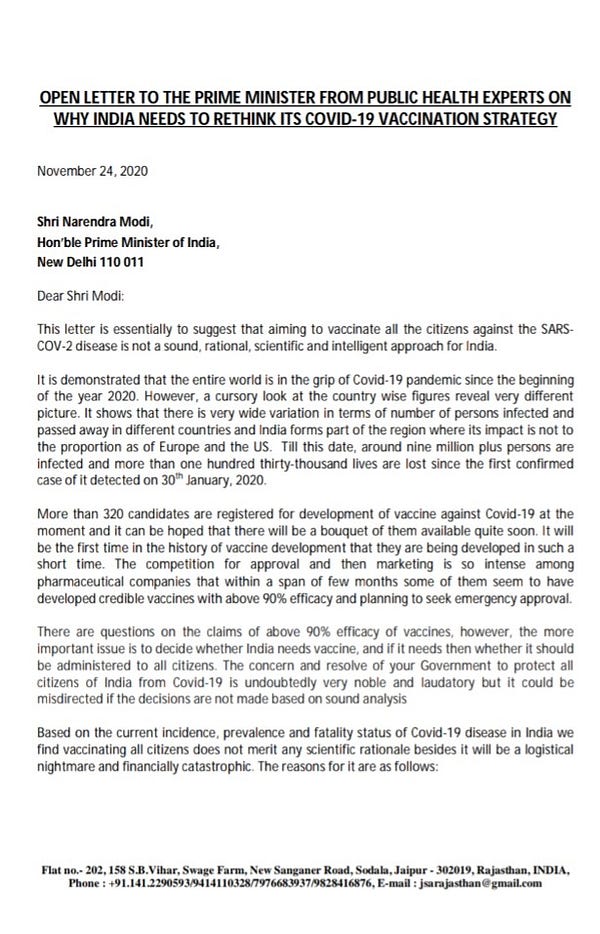

Recently, a group of Public Health wrote an open letter asking the government to rethink its strategy of vaccinating every citizen.

Now, I am obviously in no position to counter their claims or question their motives. As someone who obsesses over information though, I can see this vocabulary being adapted by ‘sceptics’. There is a tweet with hashtags like SayNoToVaccines, SCAMdemic and Plandemic in the quote tweets. Some of these points already (such as the ‘novelty’ of the mRNA platform) are. That isn’t to say these points shouldn’t be raised - but we should be aware of the effects they can have.

Venkat Ananth pointed this out on Twitter:

This poses all sorts of problems for genuine questions being raised about India’s vaccination plans. Thanks, 2020!

The government, on its part, has clarified that it was ‘never’ their strategy to vaccinate every citizen. (aside: the quote tweets are indicative of the trust-deficit that exists today)

If you look for it, on Indian Social Media, doubts/conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 vaccine exist already. These posts may not be getting a lot of ‘engagement’ today. That doesn’t mean there are no effects (Facebook argues, engagement does not equal effects) Tommy Shane of FirstDraft uses the recent debate over Facebook’s Top 10 to highlight what we could be missing in social media analysis currently.

There’s been a lot of debate recently about “ Facebook’s Top 10 ,” a Twitter account that lists “the top-performing link posts by U.S. Facebook pages in the last 24 hours,” managed by The New York Times’ Kevin Roose.

Given that conservative pages tend to dominate the results, the lists have been used to argue that Facebook is biased in favor of conservatives. Facebook, in turn, has pushed back, arguing that engagement doesn’t equal reach.

Irrespective of this argument, “Facebook’s Top 10” points to wider issues about what we see and don’t see in misinformation research. And they go beyond what data we can access, and which metrics we look at.

How do analytics dashboards shape what we see online? What if, by focusing on posts with the greatest engagement, we are missing the things bubbling underneath? Could we be looking in the wrong places and missing real harm, simply because our tools make some things harder to investigate and study?

He refers to this as the misinformation “twilight zone”. Tellingly, these questions came up as the team was investigating vaccine narratives on social media. ‘This maritime comparison’, he says, ‘is a reminder that our technology can draw us toward seeing some things and not others.’

Brandy Zadrozny’s NBC News article points out that even though Facebook took action against large anti-vaccine groups, their effects lives on.

While researchers of extremism and public health advocates see the removal of the largest anti-vaccination accounts as mostly positive, new research shows the bigger threat to public trust in a Covid-19 vaccine comes from smaller, better-connected Facebook groups that gravitated to anti-vaccination messaging in recent months.

The article also carries a quote from Renée DiResta that got my attention:

“The anti-vaccine movement recognized that [Covid-19] was an opportunity to create content, so when people were searching for it, they would find anti-vaccine content,” she said. “They saw this as an opportunity not only to erode confidence in the Covid vaccine, but also to make people hesitant about routine childhood immunizations, as well.”

So let’s round this out:

We have an information ecosystem where narratives flow across national boundaries like they don’t exist (because, on the internet, they don’t - for now anyway). Heck, we have a ‘vibrant domestic disinformation’ industry too.

There will be many questions raised about COVID-19 vaccines for reasons varying from genuine doubts to opportunism.

Such content already exists in India. Though it may be low engagement for now, we cannot guarantee that it will a) remain low engagement b) isn’t already having isolated effects.

That ‘Pharma is profiteering’ is a narrative that also already exists in India. Again, this maybe borne out of genuine concern but the talking points can be picked up and used by anyone else.

The Ipsos survey points to the existence of a belief that vaccination is not necessary, at least month some people (even if we thing that the 52% number overstates this a bit)

There is a huge information vacuum- adverse affects from any of the vaccines, even logistical issues will be used immediately to sow doubts.

Yes, I am indulging in some Doom Propheting. As of now, we are fortunate that vaccine-scepticism is not a thing in India. But, if there was ever a perfect storm for it to take roots - We are there. How we respond is going to be important.

UK is calling in the army to defend against anti-vaccination propaganda.

The Indian government is looking to “maximise involvement of local influencers, including religious leaders, for countering misinformation and rumour-mongering regarding coronavirus immunisation.”

Fortunately, we have the benefit of seeing how some of this has played out in other parts of the world. Plus, a number of platforms are actually acting against this content now (For example, I had to click through a few prompts and pop-ups before I could see vaccine related results on Instagram)

It likely won’t play out in the exact same way here - but maybe, just maybe, we can be better prepared to limit the harm.

Doom Profits

From Doom-propheting, let’s move to doom-profiting. Yes, I am talking about social media platforms. No, I am not talking about social media platforms, only.

For those of us who track this closely, the assertion that the biggest problem with social media is the business model, isn’t new. This week, Robin Harris breaks down this problem for us in ZDNet. Kyle Daly, in Axios using research from Global Witness states that ‘(a)mericans saw more political ads on Facebook in the week before the 2020 election than they did the prior week despite the company’s blackout on new political ads during that period’. He does, accurately, point out that the move wasn’t really to reduce the reach of political advertising, overall. Rather, it would prevent ads with misleading messages being thrown into the mix during what was expected to be an uncertain period.

But here’s the thing. Whether we like it or not, the advertising model is deeply entrenched in the internet of today. If we want to successfully move away from it, a “burn it all down” approach may not be the way we want to go.

Tim Hwang, in Subprime Attention Crisis talks about some of effects of a ‘sustained depression’ in the advertising markets.

Major scientific breakthroughs, like recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, have largely been made possible by a handful of corporations, many of which derive the vast majority of their wealth from online programmatic advertising.

Paywalls rising throughout the web would exclude large populations of consumers unable to afford services that until recently were free. A failure of the online advertising markets would have a serious impact on a wide range of journalists, videographers, and other media creators great and small.

changing business model that prioritized subscription and paid access would narrow these prospects and make content creation less sustainable. Not to mention the knock-on effects that might emerge from a radical slowing of the spigot of philanthropic funding—from supporting medical research to fighting climate change—driven by a contraction of wealth in the technology sector.

a sustained depression in the global programmatic advertising marketplace would pose some thorny questions not entirely unlike those faced by the government during the darkest days of the 2008 financial crisis. Are advertising-reliant services like social media platforms, search engines, and video streaming so important to the regular functioning of society and the economy that they need to be supported lest they take down other parts of the economy with them? Are they, in some sense, “too big to fail”?

Remember TikTok? Varsha Bansal wrote about the slew of Indian apps seeking to replace it. I’m calling this new ecosystem Splint-tok. What’s clear is that none of them have, so far anyway, been able to garner the same attention as TikTok seemed to have, nor generate the same kind of returns for content creators (whether that model was sustainable is another matter and the subject of Tim Hwang’s book). But what stood out to me was this seeming standardisation of social media.

Indian TikTok’s Shekhar and Sharma had similar ambitions. They wanted to transform Indian TikTok into a social media platform that combines features of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and, of course, TikTok. “We want all the social media features on this one platform so that users don’t have to go anywhere else,” says Shekhar.

And, as Sara Fischer from Axios points out, all social media companies are starting to look the same anyway.

Of this Standardisation, Tim Hwang says

Standardization has made attention an abstract, economic asset as well. It is now possible to purchase attention in the marketplaces without knowing where and how that attention was produced.

He goes on to link this standardisation to commodification,

advertising, too, has become increasingly commodified and “at arm’s length” in its design. By and large, long-term relationships do not characterize the transactions that take place in the real-time bidding systems for allocating advertising inventory…. Indeed, the goal of dominant players like Facebook and Google is to make buying attention on their platforms as “self-serve” and automated as possible. As in the financial markets, commodification has led to a massive increase in the size and interconnectedness of advertising markets and has allowed a much broader set of actors to participate.

This leads to opacity:

The measurability of the online ad economy is an inch wide and a mile deep. As such, the tidal wave of data that has accompanied the development of online advertising provides only an illusion of greater transparency.

Ultimately, he says that advertising packages attention, it is not attention itself. And draws parallels with the subprime crisis of the 2000s.

This divergence between the asset being bought—ad inventory—and the asset underlying it that defines its value—attention—directly parallels what happened to collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) during the 2007–2008 crisis.

WAIT! Prateek, why are you ranting about this?

Ok, I’ll cut to the chase. The main contention is that internet advertising is a bubble with poor fundamentals:

First, an advertising-driven online economy relies on effectively invading the privacy of consumers, a model that critics have labeled “surveillance capitalism.”1 Second, incentives exist for online platforms to continuously manipulate user behavior and seize user attention in ways that may be harmful to mental health and personal development.2 Third, online advertising incentives promote the creation of media that is shocking or reaffirming to the viewer, producing polarization and supporting the formation of echo chambers.3

That is waiting to pop.

Digital marketing is succeeding in spite of the deep structural issues of fraud, opacity, and falling effectiveness. The shrinking of legacy advertising channels has produced a stream of dollars largely unresponsive to these problems. At the same time, agencies and ad technology companies face perverse incentives to avoid slowing this flow of dollars and, quite the opposite, work to constantly juice the marketplace. The result is that the market for digital advertising grows, divorced from the reality of how ads are actually functioning.

And when that happens, there will collateral damage online and offline - CD-OO, if you will. So we should be thinking ‘phase it out’ not ‘burn it down’.

The ‘Right’ kind of Social Media comes to India

No, no, you haven’t just stumbled on to a section that will suggest how to magically reform social media. First, let’s go back a week or so. Renée DiResta writes about right-wing social media’s divorce from reality.

The major social-media platforms—which for years boosted sensational propaganda and Trump-friendly conspiracy theories such as QAnon—have been remarkably active and admirably transparent in preventing the spread of misinformation about the 2020 election

Yet reducing the supply of misinformation doesn’t eliminate the demand.

On the subject of Parler, she says:

If successful, the app is likely to reinforce hyper-partisan, bespoke realities, in which people inside each bubble barely even encounter information that might challenge their preconceptions. An open question, though, is whether the most extreme and conspiratorial communities can expand their membership if Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube refuse to let them spread misinformation.

Bryan Parker did a walk-about on the Twitter-esque Parler if you’re interested. There’s also MeWe which now claims to have 12 million users, compared with Parler which saysit has 4 million active users and 8 million total users. Gab’s, in a May 2020 filing with the SEC, stated it had 3.7 million monthly visitors.

Now, enter Tooter, which bills itself as being a part of the ‘Swadeshi Andolan 2.0’. It is based on Gab (pro version and all). Sushovan Sircar christened it “’Yet Another Repackaged ‘Swadeshi’ App Not ‘Made in India’”. To the extent, that it possible to see gab’s fingerprints just be looking the request and response headers. Even its Terms of Service flitted between Pennsylvania and Telangana.

It received some flattering coverage, being immediately labeled a Twitter alternative. But for those who remember the great Mastodon (non)migration of 2019, and the draw of conflict-based engagement - you’d be right to be sceptical. Heck, even many Parler advocates, seem to post more on Twitter as of now. That does not mean, though, that it will be always be the case.

Worth noting, though, that a number of senior BJP leaders had ‘verified’ accounts that mirrored their Twitter content. Quint wrote about 12 politicians and actors who had accounts.

Political Super-spreaders

Protests are afoot in India. So, you know what that means. Information disorder content is a higher growth industry than it normally is. Himanshi Dahiya has a thread running rounding some of these up:

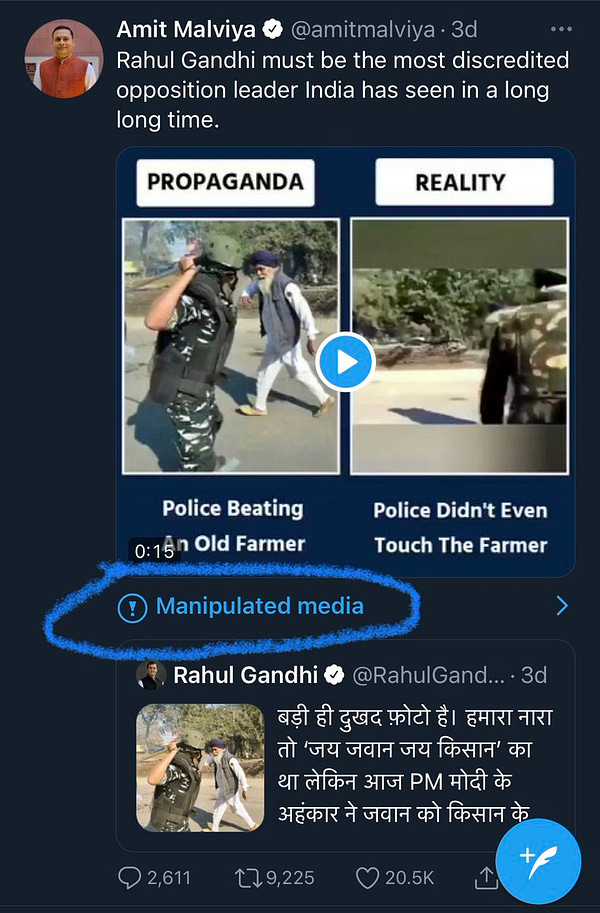

Significantly, in possibly a first of its kind intervention outside the U.S. Twitter has labeled a post by Amit Malviya as containing manipulated media. It also flagged the tweet that first posted the video (Political Kida 2- self described as the backup account of Political Kida)

This is a pretty significant moment (so significant that I said significant 2..er 4 times), so I literally created one [a moment] on Twitter, attempting to track all labeled tweets in India going forward. It is 1-tweet long, as of now, thank you very much.

But, let’s look at the ’Synthetic and manipulated media’ policy under which Twitter has taken action and this content simultaneously.

The first consideration is whether the content is synthetic or manipulated.

In assessing whether media have been significantly and deceptively altered or fabricated, some of the factors we consider include:

whether the content has been substantially edited in a manner that fundamentally alters its composition, sequence, timing, or framing;

any visual or auditory information (such as new video frames, overdubbed audio, or modified subtitles) that has been added or removed; and

whether media depicting a real person have been fabricated or simulated

Multiple fact-checking (BoomLive, Altnews, TheQuint to name just a few) sites have pointed to the existence of a longer video, parts of which were removed from the tweet in question. If you read just these bullet points, it seems like cropping a portion of the video may not necessarily be a flag. But the post detailing the policy goes on to explain that :

Subtler forms of manipulated media, such as isolative editing, omission of context, or presentation with false context, may be labeled or removed on a case-by-case basis.

Now, how does Twitter determine that content was manipulated?

In order to determine if media have been significantly and deceptively altered or fabricated, we may use our own technology or receive reports through partnerships with third parties.

In this case, we don’t know if Twitter conducted its own analysis - which could mean also checking the longer video available for manipulation, or solely relied on the published fact-checks.

But, Prateek, why are you always finding issues!

Ha, sorry, I am like this only. But seriously, the reason I am going down this rabbit hole is that it is essential to understand why platforms take actions and hold them to those principles as best as possible. Otherwise, we’re just looking at being passive spectators from one seemingly arbitrary action to the next.

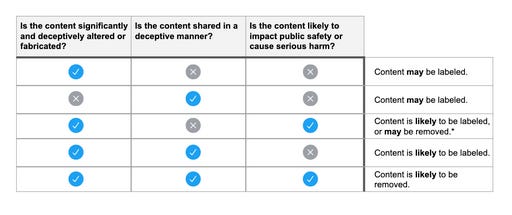

Also, I am not done yet. We still have to look into 2 additional criteria, and a little table they’ve drawn up to summarise how they are likely to take action.

The 2nd criteria, is whether content was shared in a deceptive manner.

(we) consider whether the context in which media are shared could result in confusion or misunderstanding or suggests a deliberate intent to deceive people about the nature or origin of the content, for example by falsely claiming that it depicts reality.

Now, you could say that ‘falsely claiming that it depicts reality’ checks out in this case. Or, you could say that it merely points out that the armed personnel in Rahul Gandhi’s tweet did not strike the elderly gentleman in the frame. He was struck by another armed personnel, a few seconds earlier. And, people will say this (they already are!) - which is why it is important that Twitter also be more transparent about how and why they acted.

The 3rd criteria is whether the content is likely to impact public safety or cause serious harm. Given that there are mass protests underway, I am taking a guess that Twitter could have felt there was some risk here.

The section also says:

we will err toward removal in borderline cases that might otherwise not violate existing rules for Tweets that include synthetic or manipulated media.

Next, let’s look at the table I spoke off:

This is where it becomes a lot more fun. Given that the content was not removed, we can assume that Twitter feels the post checked no more than 2 of these 3 criteria. I am fairly confident it satisfied the first criteria, the open question is which of the other 2 Twitter felt it met. That’s the difference between ‘likely to be labeled or may be removed’ and just ‘likely to be labeled’. That difference is important because I would have expected them to err on the side or removal.

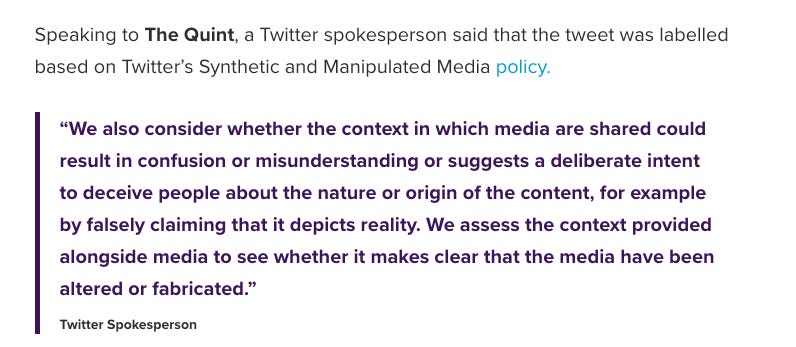

Twitter did respond to TheQuint:

Assuming this was the whole statement, and since this basically a copy-paste of criteria 2 - we can assume Twitter felt that it was met as well. Which could mean, that a combination of the content and context (protests) did not push the needle far enough to check criteria 3. 🤷♂️

Why is this significant? Because, it will go some way in establishing precedent. Assuming, of course, that this isn’t a one and done.

As of writing this, Amit Malviya himself hasn’t reacted yet. But there will be a backlash. I was only half-joking when I tweeted this:

Many Twitter users are celebrating this. And look, I have been very vocal about the difference in actions by social media platforms between US/Western Europe and India + Global South. As some one who tracks fact-checking, I can see the positives.

But, as someone who tracks the information ecosystem, I can see the pitfalls too - more positive feedback loops of conflict which are probably net-negatives (like in Edition 16).

Effects are always, always, ambivalent.

Indeed, the narrative of election interference in India is already being spun 😳.

Oh, and if you’re still with me. Applications for January 2021 cohort for Takshashila’s courses are open.

P.S. The Technology and Policy program, among many other things, includes me talking about Information Disorder. 😃

Good one, Prateek.

I feel we give too much importance to Social Media Platforms. Neither it doesn't represent the diverse voices of civil society nor it brings the right kind of argument.

But certainly, it is an ugly avatar A part of Society + Technology + Automation.

That being said, marking tweets with labels is that kind of slippery slope that social media should not get into IMO. It is a private entity that doesn't have authority unless given democratically by the people. This is a dangerous precedent and soon, Twitter will realize it.